Authors’ Note: This article is the result of a months-long project to map out the state and outlook of the legal technology sector in Singapore, and furthers LawTech.Asia’s fundamental purpose of improving awareness, knowledge and interest in legal technology. LawTech.Asia intends for this article to be a helpful piece for legal professionals, legal technologists and law students to have a bird’s eye-view of legal technology in Singapore, and to assist in the building of a thriving legal tech community in Singapore.

While intended to be extensive, the article does not purport to be exhaustive or authoritative, or to express the position of any particular organisation or initiative. This article will be a neutral “living document” that will continue to be updated as more news comes to the fore.

At the outset, the authors wish to express thanks for the innumerable sources of information available online, without which this project would not have been possible. Any mistakes herein remain the authors’ own.

Introduction

Legal technology (or “legal tech”) is technology that enables a legal services provider to better provide value to any person involved in understanding or applying the law. It can range from traditional legal research platforms and e-Filing systems, to smart contracts and document proofreading software with natural language processing algorithms.

While there has been a significant amount of activity involving the legal technology sector in Singapore, we believe that a trace of the legal tech revolution thus far will reveal the next stage of the legal tech revolution in Singapore – that is, a stage of consolidation. Before elaborating on this point, however, this article will strive to cover the following points:

- The development of legal technology in Singapore seen in two parts – the history of technology adoption in Singapore’s legal industry, and the start of the legal tech revolution in Singapore and forces influencing its development;

- A brief sketch of the legal technology sector in Singapore, including a map of the legal tech solution-provider market;

- A conclusion on the next stage of the legal tech revolution in the next 5 years.

LawTech.Asia first published this piece, “Legal Tech in Singapore”, on 21 October 2018, to trace the legal tech revolution in Singapore and to consolidate the various developments here. LawTech.Asia envisions this article as not setting out the state of play of the legal tech industry as set in stone, but as a “living document” that can and will continue to be updated as the next chapter of Singapore’s legal tech revolution unfolds. This present article updates our earlier piece based on recent developments.

The development of legal technology in Singapore

(A) History of technology adoption in Singapore’s legal industry

Recent statements on how Singapore’s legal sector has been slow to adopt technology and embrace disruption could give one the impression of a techno-phobic local legal profession.

In fairness, however, the relatively slower pace of adoption of legal technology in Singapore’s legal profession as compared to other jurisdictions (such as in the United States or in the United Kingdom) says little about the efforts of Singapore’s legal profession to utilise technology in legal practice over the last few decades.

While there is little publicly-available data on how advanced (or not) Singapore’s legal profession has been in adopting technology, certain points may be gleaned anecdotally from publicly-available sources. For instance, information from public statements and reports released by the Singapore Government (including the Singapore Courts and the Ministry of Law) shows that the Government has been actively embracing, if not spearheading, efforts to adopt technology in legal practice. This has been especially so since the establishment of an autochthonous legal system in the early 1990s. In fact, it has been publicly noted that the Singapore Judiciary has historically led the profession in “meeting both the challenges and opportunities presented by technology”.

These efforts by the Government to adopt technology have also had a cascade effect that encouraged local law firms to adopt technology-based practices. For instance, local law firms would have had to develop some form of document management system to allow them to work with the electronic systems (such as the e-Filing system) of the Singapore Courts.

Three technological initiatives by the public sector (specifically, the Courts and the Singapore Academy of Law), in particular, stand out as hallmarks of the adoption of technology in Singapore’s legal sector:

- LawNet. In 1990, the adoption of LawNet heralded the transition of legal research to the online realm. LawNet is viewed as a “one-stop centre for various information repositories”. It contains databases on case law, Singapore legislation, Singapore parliamentary debates, criminal sentencing information, registration of companies and businesses, intellectual property and conveyancing. LawNet allowed such information to be accessed from any place, at any time, providing never-before-seen convenience and efficiency in legal research.

- Technology Courts. In 1995, the Singapore Courts launched the first of several Technology Courts. These were specialized courtrooms that incorporated a wide variety of computer systems and the latest audio-visual equipment. The courtrooms also hosted a computer network that allowed the various computers in the courtroom to be linked – allowing, for instance, for multiple computers to display the same document at the same time. The Technology Courts also allowed lawyers to present cases using multimedia tools, and came equipped with computer-based transcription facilities allowing testimonies to be digitally recorded. These technologies provided a “better way of presenting complex cases involving voluminous documents which are often difficult to manage and present”.

- Electronic Filing System. In 1997, the Singapore Courts embraced online dispute resolution (ODR) when the Electronic Filing System (“EFS”) was progressively adopted. By 2000, the EFS applied to all civil litigation processes in Singapore and all local law firms. The EFS, which acted as a fully-electronic civil registry, was the first nationwide paperless court document system to be adopted in the world. The EFS enabled lawyers to commence cases and file court documents entirely online. This eliminated the need to present paper documents in court.

In 2013, the EFS was upgraded to the eLitigation system, with faster, more secure, and more streamlined capabilities.

These developments came together with smaller, yet no less significant, changes in how Singapore’s lawyers were performing legal work. The increasing adoption of the personal computer, for example, made word-processing (previously performed by secretaries on typewriters) a far more efficient endeavour. The use of e-mail meant that letters could be delivered and received instantaneously. As a further example, the rise of the Internet increasingly brought legal research (previously confined to the courts’ or law firms’ libraries) online.

While these changes were significant over the long-term, they could nevertheless be described as “incremental”. As will be apparent, these technologies do not hold the same promise of disruption that modern technologies do.

(B) The start of the legal technology revolution in Singapore and forces influencing its development

While it may be difficult to pinpoint a precise moment when the present climate of embracing legal technology (perhaps more accurately described as a “legal tech revolution”) began in Singapore, the unique importance of the public legal sector in driving legal innovation means that statements from the public sector can provide a gauge on when consciousness about the legal tech revolution began to take root.

These public statements evince a broad outline of the three key stages of the legal tech revolution in Singapore thus far:

- Recognition and assessment of the impact of technology on practice by the government;

- Signalling the importance of technology adoption and active support for technology adoption by the government;

- Generation of ground-up initiatives for legal tech adoption.

The narrative below has been presented as a chronological, linear process (from recognition (stage 1) and support (stage 2) for legal tech, leading to adoption by the legal profession (stage 3). It is crucial, however, to stress that in reality, the development and adoption of legal technology is fluid: each season sees changes in the stakeholders, products and events involved. The process is also often circular, with adoption of certain technologies calling for more in-depth assessment of its impact, leading to more support and adoption.

Below are some of the key events that have been instrumental in developing Singapore’s legal technology ecosystem. The section further below sets out the technological trends that have inspired the rise of legal technology in Singapore.

(1) Recognition and assessment of the impact of technology on practice by the government

A scan of Parliamentary speeches shows that there appears to be a watershed moment sometime around 2015, when legislators recognised in Parliament the impact of technology on the changing nature of legal practice globally, and the need for local law firms to embrace technology.

In then-Senior Minister of State (“SMS”) Indranee Rajah’s response to questions about the changing nature of practice during the annual Committee of Supply debate, she indicated that the Government was aware of the impact of technology on legal practice, and was taking steps to assess the scale of technology’s impact on the delivery of legal services in the future.

In 2016, too, the Minister for Law K Shanmugam noted the effects of technology on small and mid-sized law firms, and that the Ministry of Law was taking steps to support these firms. Minister Shanmugam informed Parliament that the Ministry of Law was working with the Law Society of Singapore to strengthen small- and medium-sized law firms, and in particular, to provide support in terms of how such law firms could access and use technology.

Efforts by the Singapore Courts to assess the impending impact of new technologies on court work were also afoot. In his Opening of Legal Year (“OLY”) 2016 speech, Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon shared about the forming of a “Courts of the Future Taskforce”, a strategic study that would form the foundation block of the Singapore Court’s approach towards the adoption of technology in court work. Menon CJ said that the Taskforce would “undertake a strategic study on getting our courts ‘future-ready'”, and would focus on “anticipating the future needs of court users and developing strategies to meet these technologies”, with the hope of providing its recommendations by the end of 2016.

Throughout 2018 and 2019, the government continued to deepen efforts to assess the impact of technology on practice. In March 2018, the Future Law Innovation Programme (“FLIP“) (introduced in more detail below) released a report titled “101 Problem Statements – Challenges & Opportunities for the Legal Sector”, which consolidated the views of legal professionals and users of legal services on the most pressing issues in the legal sector. The aim of the report was to “serve as a guide for technologists, entrepreneurs and LegalTech to develop client-centric solutions”. In January 2019, the Law Society (with co-founding from the Ministry of Law) published the results of the “Legal Industry Technology Study Report”, a survey commissioned to assess the current level of technology adoption in Singapore law firms. As the legal tech revolution unfolded, continuous assessment by the public sector has been key to ensuring that its initiatives adequately addressed the needs of the industry.

(2) Signalling the importance of technology adoption and active support for technology adoption by the government

Starting from 2017, there appeared to be a clear evolution in the stance taken by the public legal sector towards the adoption of technology. In this phase, the stance shifted from the mere assessment of the impact of technology towards the signallingof the importance of technology and active support for its adoption. The signalling could be seen in events such as the unveiling of the Singapore Academy of Law’s Legal Technology Vision, while active support came in the form of initiatives such as the setting up of FLIP and the Tech Start for Law initiative. In particular, this phase comprises:

- Statements from the Government;

- Statements from the Judiciary;

- Initiatives to support the adoption of technology in practice;

- Creation of legal tech office-holders;

- Development of tech-related curricula in local law schools; and

- Notable events and conferences (organised by the government).

(i) Statements from the Government

While there had been regular updates about the adoption of technology by international and local large law firms, there appeared to be some concern about the relative lack of appreciation of the changing nature of legal practice amongst some smaller- and medium-sized law firms. To that end, public statements from the Government hinted at the need to be mindful of these changes. The Government also commenced initiatives to support the adoption of technology to increase productivity and competitiveness.

For instance, during the Committee of Supply debate in Parliament in 2017, Minister for Law K Shanmugam shared that a study conducted by the Ministry of Law had revealed technology adoption as a key area of development for small and medium law firms. This was especially because smaller firms faced challenges in keeping up with investments into rapidly-evolving technologies. To deal with this, the Minister shared that:

We will provide the necessary partnership, framework, support and incentives. The legal profession and the private sector have to come into that partnership, embrace the changes, grasp the opportunities – some of it is disruptive. They really have to keep up with the developments in ASEAN and beyond, and strive to understand the regional market and distinguish themselves by the quality of their work and their business acumen – because a fair part of the law is becoming commoditised through technology.

Shanmugam, K (3 March 2017). “Parliamentary Speeches, Committee of Supply Debate 2017, Head R (Ministry of Law)”. Singapore Parliamentary Reports.

Recognising also that law students would have to be mindful of the changing nature of practice, then-SMS Indranee Rajah noted that some Singapore law students had already taken steps to develop multi-disciplinary and practice-oriented skills. She noted that a common interest in legal technology and innovation had led a group of students from a local university, the National University of Singapore, to start an initiative called “Alt+Law” that aspired to change the legal industry by exploring technology solutions for work performed by lawyers, and called for the cultivation and encouragement of such innovative and cross-disciplinary efforts.

(ii) Statements from the Judiciary

The Singapore Judiciary also took steps to signal the changes to practice caused by technology. In his OLY 2017 speech, Menon CJ noted that the Singapore legal industry had thus far taken an incremental approach towards assimilating technology into legal work. In particular, Menon CJ noted initiatives such as e-filing, e-discovery tools, the use of video-conferencing for hearings, LawNet, and the Singapore Law Watch website. Menon CJ shared, however, that:

(T)he fact is that the practice of law has not experienced disruption to the same extent that other industries and professions have.

Opening of the Legal Year 2017, Response by Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

Menon CJ suggested that this could be due to two reasons: First, technology had only recently reached a tipping point where it could be applied meaningfully to legal work; and second, because lawyers “are notoriously resistant to change – perhaps an inevitable characteristic of a profession whose principal function is to uphold an enduring and stable system of rules around which society can structure its interactions”.

Menon CJ also shared about various practice areas which could be fundamentally disrupted by technological developments:

(a) Dispute resolution. Menon CJ pointed out that online dispute resolution (“ODR”) platforms would allow court users to resolve disputes through a blend of dispute resolution mechanisms (such as mediation and arbitration) online, and with the aid of artificial intelligence. Menon CJ also noted the potential of ODR to expand into and disrupt other fields of dispute resolution.

(b) Basic corporate work. Menon CJ also noted how freely-available data, data analytics and blockchain technologies would provide reliable and readily-accessible standard precedents, thus greatly expediting transactions in real estate, employment and procurement.

More generally, Menon CJ said that technologies and phenomena like predictive tools, video-communications technology, and increased rapid information flows would impact the fundamental structure of the legal system, such as how younger lawyers are worked and trained, how court hearings will be conducted, and how legal work is requested and provided.

In this vein, Menon CJ urged the legal profession to embark on a continuous drive to improve the quality and provision of legal services with the help of technology, saying that “it would be wrong to approach technology as if it is something to be vanquished just because it threatens to disrupt or challenge how we (lawyers) have been accustomed to operate”.

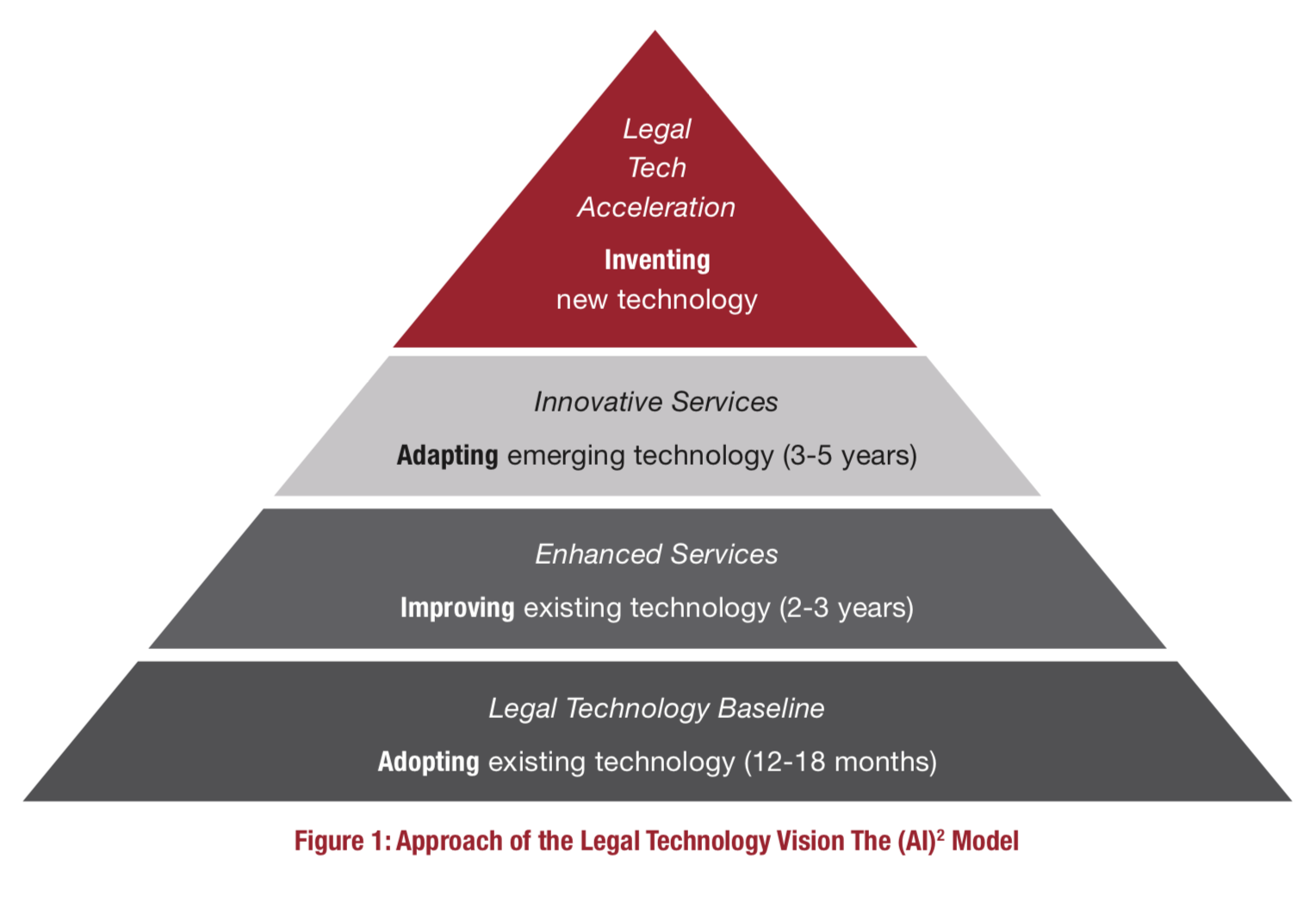

Most importantly, Menon CJ unveiled the Singapore Academy of Law’s (“SAL”) Legal Technology Vision. The Legal Technology Vision set out in a single document SAL’s vision for how legal technology would be adopted and incubated as an industry in Singapore, and a developmental road map for the legal technology industry in the next five years. The Legal Technology Vision was a significant milestone for Singapore’s legal profession and legal technology community in the following ways:

(1) It was a timely and strong reminder to local legal professionals that the industry was ripe for disruption, while signalling that help and assistance would be available for law firms willing to embrace new modus operandi.

(2) It signalled the seriousness of the Ministry of Law, the Judiciary, SAL and the Law Society of Singapore (the representative body of Singapore’s legal profession) in using technology to improve legal services in Singapore and to develop Singapore as a legal services and legal technology hub.

(3) The Vision provided a tangible road-map highlighting the timeframe and milestones based on which the local legal technology sector would be able to pace and evaluate its development.

Continuing along this vein, Menon CJ devoted a significant part of his 2019 OLY speech to addressing how technology would change the legal profession. He highlighted “three foundational aspects of legal practice that we can expect to be profoundly impacted”:

- Design of courts and dispute resolution mechanisms: Disputes are being increasingly resolved online, and with the assistance of AI;

- Development of the law: Established principles of law will come under scrutiny and change in an age of “smart contracts, virtual properties, driverless vehicles and automated artistic works”;

- Practice of law and demand for legal services: Technology will significant reduce the demand for certain types of legal work, which can be outsourced to alternative service providers.

To this end, Menon CJ suggested “three possible areas of focus for reforming, reimagining and remodelling our profession”:

- Legal education: Menon CJ indicated that conversations are underway to reform the legal education landscape to better equip students with the knowledge needed in the contemporary legal practice;

- Professional training of lawyers: In strong terms, Menon CJ stated that “We cannot be content with piecemeal and modest efforts; instead, we must reimagine new and creative ways by which we may raise our professional standards and skills in the current milieu.”

- Transformation and innovation within the Judiciary: A number of initiatives under the Courts of the Future Taskforce were highlighted, such as the development of an online dispute resolution platform for motor accident claims, as well as the formation of an Office of Transformation and Innovation within the Judiciary itself.

In April 2019, Menon CJ spoke again on the importance of reform in the legal profession at the gala dinner of the Inter-Pacific Bar Association Annual Meeting and Conference. In his speech, Menon CJ urged the legal profession to seize the moment and be at the front line of technological change. He expounded on a similar theme in his Mass Call Address 2019, where he warned that technology has already begun to displace lawyers from some areas of practice, and urged the legal profession to “reskill” to adapt to this new reality.

The statements highlighted above by the Government and Judiciary are not exhaustive: ministers and judges are frequently invited to speak at a multitude of events, and in recent times technology has become a recurring topic in these speeches, particularly as the Government and the Judiciary strives to push the legal profession towards greater technology adoption.

(iii) Assistance schemes to support the adoption of technology in practice

Since the launch of the Vision, the Government (in conjunction with professional bodies, such as the Law Society of Singapore) has rolled out several schemes and programmes to support technology adoption and innovation in legal practice. These are covered briefly below.

(a) FLIP

FLIP is a two-year pilot programme commenced in January 2018 to support technology adoption in law practices, support legal technology start ups, and build a community and ecosystem for legal technology. FLIP itself comprised of three elements: first, a Legal Innovation Lab located at the Collision 8 co-working space (itself just opposite the Supreme Court); second, a virtual collaboration platform called “LawNet Community”; and third, the first legal technology accelerator in Southeast Asia to groom promising legal technology start-ups.

Signing up for FLIP opens up the opportunity to join any of three tracks: “Lighten-up!” for smaller law firms looking to leverage technology to maximise efficiencies in practice; “Ideate!”, which brings together law firms and legal technology startups to collaborate on legal innovation, and “Accelerate!”, a 100-day acceleration programme to help promising legal technology startups scale up their business. By its opening, 23 entities had signed up for FLIP. These included large law firms Rajah & Tann Singapore LLP and Dentons Rodyk & Davidson, small law firms ECYT Law LLC and Consigclear LLC, and legal technology enterprises such as LexQuanta, SingaporeLegalAdvice.com, and Zegal (formerly Dragon Law).

In July 2019, FLIP launched Asia’s first legal tech accelerator in Singapore, GLIDE. GLIDE is a national legal tech accelerator program connecting high growth legal tech and reg tech entrepreneurs with law firms, law schools and legal industry professionals in a bid to revolutionise Asia’s legal industry. The applications are open to selected startups, both local and overseas, with primary focus in artificial intelligence, blockchain, advanced analytics, automated data collection and analysis. Beyond scaling startups, it hopes to hone the “intra-prenuership” of in-house legal capabilities by being a catalyst for co-creation of legal tech solutions. By attracting high-potential startups, its goal remains to drive technological innovation in Singapore’s legal scene.

(B) TECH START FOR LAW

In February 2017, the Ministry of Law, the Law Society of Singapore and SPRING Singapore announced the Tech Start for Law initiative, a funding programme that assisted Singapore law firms in adopting technology.

Under the programme, law firms that began adopting selected technology solutions in areas such as practice management, online research, online marketing would be provided with funding support of up to 70% of the first-year cost of adopting the selected technology products. The five technology products covered under the programme were CoreMatter, Lexis Affinity, Clio, INTELLLEX and Asia Law Network. Up to S$2.8 million in funding, amounting to 380 units of these technology solutions, was made available between 1 March 2017 and 28 February 2018.

(C) BASELINE LEGAL TECHNOLOGY MANUAL

As mentioned above, the Legal Technology Vision contained a roadmap that envisioned the development of the legal technology ecosystem in Singapore. In particular, the first part of the roadmap called for the widespread adoption of a “baseline suite of legal technologies” that would act as a potential springboard for future technological development.

As a step towards realising the roadmap, the SAL developed an online manual, known as the Baseline Legal Technology Manual (the “Manual“). The Manual consisted of articles that covered “baseline” technologies useful for helping law firms improve the productivity of their practices. The articles are intended to be a “starting point for lawyers to understand baseline legal technology”. Contributors to the Manual are tech-savvy players in the legal industry making technology recommendations without any intention to endorse specific products. As of the time of writing, the Manual is still in the midst of publication. Several completed articles, however, have been published for reference on the webpage of the Manual.

(iv) TECH-CELERATE for law

In March 2019, a follow-up programme to the Tech Start for Law initiative (covered above) was launched. Named “Tech-celerate for Law“, the programme was organised by the Law Society of Singapore in conjunction with the Ministry of Law, Enterprise Singapore and the Infocomm Media Development Authority of Singapore (“IMDA“) with the aim of supporting Singapore Law Practices (“SLPs“) by partly funding (up to 70%) technology solutions. Nine technology solutions are supported, from basic technology applications like practice management, document management and online legal research systems to more advanced applications such as e-discovery, client engagement, document assembly and document review software (a full list of which can be found here). Supported by $3.68 million in funding, the ultimate goal is to assist and incentives more small and medium law firms to harness technology in remain competitive.

(v) ADVANCEMENT OF LEGAL TECH IN THE STATE COURTS

The shift of the State Courts to a new building (the “State Courts Towers“) in 2020 has presented opportunities to introduce initiatives around legal tech directly within the State Courts. FLIP at State Courts (“FAST“) aims to develop tech-enabled legal solutions that addresses existing barriers to access to justice.

In addition, the Courts will be establishing Clicks @ State Courts. Located at the 21st floor of the State Courts Towers, Clicks will offer workspaces on a rental basis and build an eco-system to promote collaborative law, innovative co-creation and foster knowledge sharing. Beyond lawyers, there will be space for tech companies, law students, stakeholders, academics, social workers to collaborate together. Moreover, the space will assist those firms in adopting technology by providing shared resources to them as they will have reduced operational costs and inefficiencies. Ultimately, the aim is to translate these productivity gains into better services and increasing access to justice for the common man.

(VI) SMARTLAW RECOGNITION SCHEME AND SMARTLAW GUILD

The SmartLaw Recognition Scheme was launched on 1 March 2017 by the Law Society to recognise SLPs which have adopted technology to improve productivity and increase business capabilities.

Subsequently, the SmartLaw Guild was launched on 15 May 2019 by the Law Society of Singapore in collaboration with the Ministry of Law, Enterprise Singapore, and IMDA for legal practices that were certified under the SmartLaw Recognition Scheme. The SmartLaw Guild is a platform to bring together like-minded law practices who wanted to reinvent themselves and future-proof their legal practices, through networking and events.

(d) Creation of legal tech office-holders

With the burgeoning of public sector efforts to drive legal tech adoption, a number of new departments have been created within the public sector to spearhead these efforts. Some of these departments are:

- The Law Society of Singapore’s Legal Productivity and Innovation Department;

- The SAL’s Legal Technology Cluster;

- The Attorney-General’s Chambers’ Legal Technology Innovation Office;

- The Supreme Court’s Office of Transformation and Innovation (Judiciary)

The creation of these specialised departments, embedded in key public legal sector institutions, reflects the Government’s commitment to support legal tech. It also indicates that there will be a steady growth in the community of persons contributing at the intersection between law and technology.

(e) Development of tech-related curricula in local law schools

In 2018, local law schools also began making significant inroads into Singapore’s legal tech scene.

One of the most exciting developments was the Singapore Management University’s (“SMU“) new degree programme in Computing & Law, jointly launched by the SMU School of Law and the SMU School of Information Systems. Commencing in August 2020, the programme seeks to develop “IT and legal professionals who are adept at bridging technology and law”, and will “equip students with skillsets in IT & business innovation, operating IT & business innovations within a legal framework, and employing IT in legal practice”. According to SMU, job positions that would be available to graduands of this programme include legal knowledge engineers and legal technologists – signalling new and potential career paths that hybrid law-and-tech professionals can venture towards.

Other initiatives include the establishment of the Centre for AI and Data Governance (“CAIDG“), a research institution which conducts independent research on policy, regulatory, governance, ethics, and other issues relating to AI and data use. SMU also launched the Graduate Certificate in LegalTech, which aims to “upskill” existing lawyers and to give participants the skills to understand and embrace new technology.

(f) Notable events and conferences

The Government (particularly through the SAL) has also organised a number of notable events and conferences.

TECHLAW.FEST

In April 2018, the SAL and events company Corp Agency organised the first edition of TechLaw.Fest. The conference brought together over 1,000 legal professionals, technologists, entrepreneurs and regulators to discuss the future of the legal industry in two key tracks: the Law of Tech Conference which tackled the topic of smart regulation of emerging technologies and the Tech of Law Exchange which explored the impact of technology on the practice of law. The conference also included an exhibition featuring legaltech vendors from Singapore and the region, as well as a hackathon on the topic of personal data protection. The closing keynote speech was made by Andrew Arruda, CEO and co-founder of ROSS Intelligence.

The second edition of TechLaw.Fest happened from 5 – 6 September 2019, and featured 40 exhibitors, 15 startups, over 1,500 attendees, and key speakers such as Minister for Law K Shanmugam, Sir Tim Berners-Lee (widely recognised as the inventor of the World Wide Web), Mr William Deckelman (Executive VP, General Counsel and Secretary of DXC Technology), and Mr Antony Cook (Regional Vice President and Chief Legal Counsel of Microsoft Asia). The theme for TechLaw.Fest 2019 was themed “The Net Effect of Data: Commerce, Connectivity and Control”, and saw discussions around the regulation and governance of data and new technologies like AI. An initiative, called the “Tech Talks” stage, also featured many of Singapore’s young drivers in the legal tech space. In addition, TechLaw.Fest 2019 also saw the launch of significant initiatives, such as the August 2019 edition of the State of Legal Innovation in the Asia Pacific Report, as well as the Asia-Pacific Legal Innovation and Technology Association.

GLOBAL LEGAL HACKATHON

From 23 to 25 February 2018, the SAL and Thomson Reuters co-organised the Singapore round of the Global Legal Hackathon, an international hackathon that engages legal industry stakeholders around the vision of rapid development of solutions to improve the legal industry world-wide. Legal tech startup Regall, which develops an AI-based file management software, was selected as one of the 14 finalists to participate in the Global Legal Hackathon Final Round Gala in New York on 21 April 2018.

In January 2019, the SAL and Singtel co-organised the Singapore edition of the Global Legal Hackathon. The theme revolved around curating a technological solution to a problem engineered for in-house counsels. Team AcidFyre won the Singapore leg for developing Clausebot, a smart knowledge assistant that provides lawyers a fast and easy way to find relevant clauses and contracts by tracking regulatory and case law changes, as well as internal policies, and updating a firm or company’s contracts database.

(3) Ground-up initiatives for legal tech adoption

As mentioned in the preceding sections, the foundations of Singapore’s legal tech revolution could be said to have been planted sometime in or around 2015, with increasing awareness of the impending disruption facing the legal industry.

Some, however, have warned that reception towards the revolution has not been as fast or as extensive as had been hoped. Indeed, the relatively slow adoption of legal technology in Singapore’s legal profession was recognised by Menon CJ, when he recently remarked that “regrettably, our response to legal technology has been lukewarm”. In a study conducted by the Law Society of Singapore in 2017, it was revealed that only 9% of small- and medium-sized SLPs used technology-enabled productivity tools. To address this, Menon CJ challenged Singapore lawyers to embark on a mindset shift to embrace, rather than resist, technology.

Nevertheless, there is no denying that there has been a significant hubbub of activity surrounding legal technology in Singapore, with at least one source suggesting that Singapore could well be the legal technology hub of Southeast Asia. The Law Society’s 2018 “Legal Technology in Singapore” survey stated that more than 2 in 5 decision-makers in law firms say that they will invest more in legal technology in the immediate future.

The section below sets out some of the law firms, organisations and initiatives that form the Singapore legal tech ecosystem. The information below is not intended to be exhaustive. LawTech.Asia will continue to update it as new information comes to the fore.

(A) Law firms championing legal technology

A number of law firms rose quickly to the government’s clarion call to increase legal tech adoption. Some law firms made use of the many government initiatives available to them. For example, when FLIP first opened, 23 entities signed up. These included large law firms Rajah & Tann Singapore LLP and Dentons Rodyk & Davidson, and small law firms ECYT Law LLC and Consigclear LLC.

Further, a number of law firms – usually international or big-sized law firms – have blazed their own trail for advanced legal tech adoption:

- Wong Partnership announced in late 2017 that they were partnering with Luminance to deploy its artificial intelligence technology to support its practice. Luminance uses advanced machine learning techniques to automatically sort, cluster and classify a data room, pinpointing even subtle differences between contracts so that hidden risks can be uncovered early on in a transaction.

- Rajah & Tann Asia (“RTA“) launched Rajah & Tann Technologies (“R&TT“) in late 2018, which offers technology-enabled legal solutions including electronic discovery (“e-discovery“), cybersecurity, data breach readiness and response, and other legaltech and regulatory technology services, to clients and the member firms of the RTA network. R&TT also acquired Legal Comet in late 2018, an AI-driven firm which offers various legal tech advisory services including e-discovery, forensic technology and data governance.

- Allen & Overy’s (“A&O“) Fuse, a legal tech incubator, was first based in their London offices. However, in late 2018, A&O hosted a Fuse AsiaWeek in Singapore, which brought together Fuse members with the local stakeholders in Singapore’s legal tech market. This signalled a possible pivot by A&O to expand Fuse’s opportunities in Singapore and Asia.

- Clifford Chance announced the launch of Create+65 in December 2018, an innovation lab located in Singapore. This was opened in conjunction with Singapore Economic Development Board and SAL’s FLIP Programme. It functions to identify, incubate, test and pilot new legal technology solutions with the aim of enhancing the firm’s and the wider industry’s service offerings to clients.

- Dentons’s Nextlaw Labs and Nextlaw Ventures have been around since 2015: Nextlaw Labs is a “legal technology and innovation advisory”, as well as its sister company Nextlaw Ventures, a “venture capital fund focused exclusively on early-stage legal technology startups”. With Dentons’s combination with local firm Rodyk, it is expected that Nextlaw Labs and Nextlaw Ventures will make waves in Singapore’s legal tech space. Already, they have sponsored the local edition of the Global Legal Hackathon.

According to an article by Artificial Lawyer, the number of incubators and accelerators are expected to grow, and so will the tech produced by law firms themselves. Singapore’s law firms are likely to pick up on these international trends as well.

(B) Student interest groups focusing on legal technology

Young law students, being a part of a generation that is very much familiar with the use of technology, have also been driving legal technology initiatives. At the beginning of Singapore’s legal tech revolution in 2015, only one student-led group focusing on legal technology was known to have existed – Alt+Law, which has been publicly mentioned in Parliament. Today, there are at least three student interest groups focusing legal technology, with more students joining these initiatives regularly. These three groups are:

- Alt+Law;

- SMU Legal Innovation and Technology Club;

- Blockchain Club @ SMU, with an arm that focuses on how blockchain is relevant for the delivery of legal solutions.

(C) Legal tech solution providers

The legal tech space is quickly being crowded with more and more solution providers, ranging from contract automation, to AI, to use of blockchain technologies in law. These will be covered in more detail below in our section on “Types of Legal Technologies”.

(B) Forces influencing the development of Singapore’s legal tech revolution

A myriad of factors, internal and external, came together to generate serious interest in technology and innovation in the legal sector. Four factors, in particular, have played a significant role:

- Liberalisation and internationalisation of Singapore’s legal industry;

- Increasing sophistication of clients;

- Technological capability; and

- Progressive changes in Singapore’s substantive laws.

(1) Liberalisation and internationalisation of Singapore’s legal industry

The first of these factors relates to the moves to liberalise and internationalise Singapore’s legal industry. In 2008, the Singapore Government made fresh moves to liberalise Singapore’s legal sector. This resulted in the introduction of schemes such as the Qualifying Foreign Law Firm (“QFLP”) and the Enhanced Joint Law Venture (“EJLV”) Schemes. The intention was to attract foreign law firms to set up practices independently or jointly (with local law firms), thereby attracting greater amounts of international legal work to Singapore. These moves coincided with other initiatives by the Singapore Government to position Singapore as a legal hub for dispute resolution (in particular, arbitration), and to promote the use of Singapore law in cross-border transactions. Given that foreign law firms were already heavily adopting technology in their work at the time, such moves meant that it was necessary for lawyers and law firms in Singapore to also adopt technology in other to compete or cooperate on level terms.

While international work may generally be considered the preserve or international or large law firms, the Government also encouraged smaller-sized law firms to leverage on technology to compete on par, at least in some areas, with large firms in the international market. In short, the liberalisation of Singapore’s legal industry created knock-on effects that encouraged the local legal profession to seriously consider the adoption of technology in their work.

(2) Increasing sophistication of clients

While not widely-documented, the increasing exposure of clients to technology-based legal practice has also exerted pressure on law firms to adopt technology. Clients who were aware of the availability of legal technology (or even being aware that large amounts of basic legal knowledge could be found online) would be more savvy about choosing law firms that could provide higher quality services at lower cost. Over time, a Darwinian-like evolution would occur, where firms that were able to use technology effectively would be trusted and hired consistently, while firms that did not (especially less-established firms) would face pressures to either adapt or leave the industry.

(3) Technological capability

In the last decade, technology has also advanced to a degree where it may be said to have reached a “tipping point”. That is to say, technology has reached a stage where its adoption in legal practice is possible as a matter of cost, scale, and effectiveness.

The possibility of technology adoption is further increased when multiple technologies can be applied in tandem to produce even more significant benefits. For example, the natural-language processing capabilities of artificial intelligence combined with the availability of hitherto unavailable large-scale data has allowed legal technology companies to be able to use AI-driven data analysis to predict case outcomes.

In another example, advances in the connectivity and reliability of communications technology has contributed to the rise of online dispute resolution. In this area, technologies such as video communications (or, in a more advanced form, “telepresence”) has allowed parties and judges to convene virtually, dispensing with the need for physical presence and effectively creating “courtrooms in cloud”.

These possibilities have led to views that the local legal industry is ripe for “Uberisation” (in other words, disruption to a scale as seen in the taxi industry). Such developments would not have been possible in the past, where concerns with reliability, cost or even availability meant that in most cases, it made more sense for law firms to hire a hard-working junior associate to do work that was tedious and time-consuming.

(4) Progressive changes in Singapore’s substantive laws

It is an oft-cited truism that regulators and the law often are playing “catch-up” with changes in technology. Indeed, as Menon CJ stated in his 2019 OLY speech, “over time, the content of the law will change as new areas of law and legal principles emerge in response to technological advancements… we will have to navigate these uncharted territories without the comfort of direct legal precedent, and we must all keep abreast of developments in technology in order to grapple with the legal issues that will come before us”.

Much to its credit, the Government has strived to keep Singapore’s law on an even pace with the rate of technological advancement. This has had a positive influence on Singapore’s legal tech market. With Singapore’s laws progressively recognizing and allowing new technologies, rather than prohibiting them, new technologies had the space to grow and develop locally.

Even before the recent legal tech revolution (which arguably began in 2015), Singapore’s laws had already progressively made provision for the use of technology in law. For example, Singapore amended its Electronic Transactions Act (“ETA”) in 2010, which recognises the use of electronic records, electronic and digital signatures, and electronic contracts. Similarly, Singapore also passed the Personal Data Protection Act in 2012, which governs the collection, use, disclosure and care of personal data.

Since 2015, and commensurate with the explosive growth of new technologies worldwide, Singapore law has kept pace with technology – thus enabling and encouraging the unfolding legal tech revolution here. Some of these changes in the law that are directly related to legal tech are detailed below:

- Passing of the Payment Services Act (“PSA”) 2019: The PSA was passed in January 2019, and at the time of writing of this article, had not yet come into force. The PSA regulates a number of payment services, including domestic and cross-border money transfers, digital payment tokens and electronic money issuance. Payment services providers subject to the PSA are required to obtain licenses, which will allow the Monetary Authority of Singapore (“MAS”) to regulate these payment service providers. The PSA also provides for some risk-mitigating provisions for the protection of consumers and merchants. The flexible and forward-looking framework of the PSA was introduced as a response to the increasing number of fintech products in Singapore, such as mobile wallets and cryptocurrency. The regulation of fintech will no doubt have an impact on legal tech as well, especially for businesses that use smart contracts or blockchain technology in their day-to-day trading activities.

- Amendments to the Supreme Court of Judicature Act (“SCJA”): In October 2018, Parliament passed amendments to the SCJA. One notable amendment is enabling court hearings to be held via electronic means, such as live video link or live television link. This means that legal proceedings do not require the physical presence of the parties or their lawyers in court, which would enhance the court process and save time. This may indicate a segway towards more online dispute resolution mechanisms put in place at the Courts, particularly for small or routine claims.

- Proposed Amendments to the Personal Data Protection Act (“PDPA”): The Personal Data Privacy Commission (“PDPC”), which administers the PDPA, has indicated in early 2019 that it intends to introduce a mandatory data breach notification regime, under which organisations will be required to notify the PDPC and affected individuals of data breaches that are “likely to result in significant harm or impact to the individuals to whom the information relates”. At the time of writing of this article, the proposed amendments to the PDPA have not been formally introduced in Parliament.

- Proposed Amendments to the ETA: In June 2019, the IMDA launched a public consultation to seek views on the review of the ETA. Some of the key areas of reform include: including more electronic transactions under the ambit of the ETA (such as contracts for immovable property, lasting powers of attorney and negotiable instruments); providing certainty over new technologies such as blockchain and smart contracts; and updating its certification authority framework to ensure currency with latest international standards. As of the time of writing of this article, the results of the public consultation had not yet been released. The proposed amendments are expected to have a significant influence on the legal tech industry – for example, property deals may soon become completely digital and paperless.

There are many other examples of Singapore’s legislators responding to advances in technology – such as the passing of the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act 2019 which regulates online “fake news”; the amendments to the Protection from Harassment Act, which, aside from protecting individuals from acts of harassment both offline and online, also provides remedies to private individuals and entities in respect of online falsehoods and online “doxxing”; the introduction of new laws to govern drones and autonomous vehicles; and progressive developments in Singapore’s intellectual property regime. However, as these are not directly related to legal tech per se, they are not covered in this article.

Technological Trends that are Driving Legal Technology

(A) Data Analytics

Data analytics refers to “the extensive use of data, statistical and quantitative analysis, explanatory and predictive models, and fact-based management to drive decisions and actions”. Today, the collection of massive amounts of data, along with data analysis techniques, make possible the unveiling tremendous insights into almost every facet of human life and the world we live in. Key to this is the existence of massive data sets – in fact, digital data has been estimated to reach 44 zettabytes (10^21 bytes) by 2025.

Big data analytics is a field that is of particular importance to Singapore. In the context of legal practice, law firms have large amounts of data (in the form of legislation, case law, and client data). The data that is stored is also increasing at an exponential rate. Big data analytics will be able to leverage on such massive data sets to reveal insights that could lead to faster discovery processes or the faster identification of relevant case law.

(B) AI and Machine Learning

Machine learning is a subset of AI in which algorithms parse large amounts of data and are able to draw their own conclusions without the need to be specifically programmed to do so. The success of such algorithms depend on the size of the data set – the larger the set, the more accurate predictions the algorithm can generate.

In Singapore, public agencies such as AI Singapore, the National Research Foundation, the Smart Nation and Digital Government Office, the Economic Development Board, and the IMDA have either been set up or given the mandate to research on AI and enhance Singapore’s AI capabilities.

(C) Blockchain

Blockchain technology refers to technology utilising decentralised electronic ledgers with duplicate copies of the same ledger stored on multiple computers in multiple places. The distributed and immutable nature of the blockchain essentially engenders trust, given that every transaction on the blockchain is displayed publicly but virtually impossible to manipulate.

Legal technology products based on blockchain technology include tamper-proof public data bases and smart contracts. For the former, the blockchain would allow for a third party intermediary to be bypassed, removing the need for a trustworthy middleman to facilitate the transaction. For the latter, the utility that blockchain technology provides is that it allows a contract to be automatically executed once certain pre-programmed conditions have been met.

Thus far, while information stored on a blockchain has yet to be adduced as relevant evidence before the Singapore courts, it has been argued that information stored on a blockchain can be used as primary evidence by virtue of section 64 of Singapore’s Evidence Act.

(D) Video-conferencing and telepresence

Modern video conferencing and telepresence technologies are a subset of advanced communication tools that could reduce and possibly virtually eliminate the need for lawyers to travel to conduct business. Significantly, non-verbal cues are not lost, thus retaining the typical advantages of meeting in person.

Types of legal technologies

This section covers some of the key legal technologies and legal technology products available in the Singapore legal technology market. Where applicable, examples of notable companies or start-ups based in Singapore (or notable legal technology companies from other countries) that provide the relevant legal technology service or product are included. The list below, while extensive, is again not intended to be exhaustive, and will continue to be updated over time.

(A) Automated contract generation

According to an article published by the Duke Law School, existing software for automated contract generation are mostly web-based, and are based upon a questionnaire style system. This means that each answer (by the user) to a questionnaire prompts a different series of follow-up questions to tailor the final document to the user’s specific needs. In turn, this provides a larger, more customisable logic tree than one focused on only a single practice area. Many of these software first require the user to upload and code a pre-existing contract. The program then uses the coded contract to generate a questionnaire, which can then be used to quickly draft similar documents. Because coding documents can be difficult, some programs code them automatically through AI.

Users of automated contract generation software (sometimes also known as document assembly software) can include lawyers, clients, or a combination of the two. In the latter scenario, a lawyer would first create the coded contract, and send the questionnaire to his client. The client then fills up the questionnaire. Finally, the lawyer reviews and finalises the contract generated by the software. This flexibility, combined with the speed at which these programs can create documents, reduces client costs and frees up lawyers’ time to focus on the key parts of the client’s contract. More advanced document assembly tools can take into account the importance of the various components of the information that is fed into it. This is called the “dynamic template”, which enables personalisation and creativity within acceptable boundaries.

An example of a legal technology company in Singapore in the field of automated contract generation is Legalese. Legalese’s software uses a domain-specific language for law (a language that is designed to capture legal semantics and logic), such that not only does it automate the process of generating legal documents, it also proves that the contracts written in the language are correct, consistent and compliant with relevant legislation. Other firms that provide automated contract generation services include Vanilla Law (with Vanilla Law Docs), Zegal, LegalFAB, and Legal Pack.

(B) Cybersecurity

With increasing digitisation and virtualisation, law firms and consumers of legal services are also increasingly at risk from cyber attacks. In addition, should these companies not take reasonable precautions to safeguard personal data, they could also find themselves in breach of the European Union’s General Data Protection Rules (“GDPR“), or Singapore’s PDPA. For these reasons, there is an increasing need for law firms to procure cybersecurity solutions to safeguard sensitive information.

(C) Due diligence software

For law firms, a key part of opening a new client’s file is to conduct a conflict search, to ensure that the law firms is not caught in a conflict of interest when acting for the prospective client. Law firms also conduct extensive due diligence checks regarding conflicts, anti-money laundering and other regulatory requirements. Due diligence software like Handshakes and Regall assist firms in search for important information relating entities and persons related to their target company (e.g. other shareholders, directors and companies they may own).

(D) E-Discovery

Electronic discovery (or e-discovery) helps law firms to identify relevant content and provides information oversight in legal cases. E-discovery solutions automate the e-discovery process, which is outlined in the Electronic Discovery Reference Model (“EDRM“) diagram. They are essential to managing the ever-changing nature of e-discovery processes. E-discovery processes, triggered by a lawsuit or internal investigation, change as litigation progresses because the nature of the dispute and individuals involved are not constant. This article introduces the EDRM diagram, describes the e-discovery process, and describes available technologies that law firms can adopt.

(E) Electronic legal research tools

Electronic legal research, which previously heralded a quantum shift in the approach towards legal research over traditional books and tomes, has been around for a longer time compared to other legal technologies listed here. Electronic legal research tools essentially allow lawyers to access legal materials – be they case law, legislation, parliamentary debates, regulatory information, or even information about clients and opposing parties – to be done entirely online, in the comfort of one’s office (or home). Electronic legal research was conventionally done through boolean searches (with a user requiring a basic understanding of logic-based connectors to be able find the information required). The advent of natural-language-driven search engines, however, have allowed search databases to be “smarter” in understanding natural language searches.

In Singapore, notable private sector companies providing electronic legal research tools are Lexis Singapore and WestLaw. LawNet, a legal research engine that counts (among other things) Singapore, Malaysian and UK case law in its database, is managed by the SAL. LawNet provides other tools as well, such as the Sentencing Information and Research Repository, which provides customisable data sets on criminal cases.

(F) Knowledge/Case/Practice Management Software

Knowledge, case or practice management software address two key needs of the legal professional: (a) consolidating the information of the law firm, and (b) helping lawyers make sense of the information so that lawyers are able to use the information more effectively.

Such software address these needs by categorising, consolidating and assisting in the management of a law firm’s information databases.

Such systems group documents with various case files for easier search and retrieval. Commonly, these systems also allow the storing and sharing of information between lawyers and teams in the law firm. Practice management software can also assist with billing and personnel management, and with the aid of data analytics and visualisation, generate insights to track the firm’s performance. Some systems even integrate into Microsoft Office through add-ons, such that any new information received can be saved directly into a case file that is managed by the system.

In this regard, many examples of such software go beyond basic keyword searches of Word and PDF documents by searching multiple sources of information (for example, emails and time entries). More sophisticated software can understand the context of documents located, and on that basis, identify even more relevant or related documents. Commonly, KM platforms are used together with practice management systems to aid lawyers in a whole range of practice and administrative work.

In Singapore, existing products include Lexis Affinity (LexisNexis), Firm Central (Thomson Reuters), CoreMatter, Narus, and NetDocs. Another example is OnePlace Solutions, which can consolidate emails and case files within one programme (Microsoft Sharepoint). As a further example, INTELLLEX provides software that manages legal information and content for easier search and retrieval. Tessaract.io (launched by Asia Law Network) is also another major product in the case management space; it is a cloud-based solution that handles workflow management, client management, knowledge management, while including features such as Optical Character Recognition and Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) calls.

(G) Legal Analytics

Legal analytics software provide data analytics solutions specifically for the legal industry. Leveraging on data analytics algorithms and AI, such software analyse documents for various insights, including potential legal risks, predictions of success, patterns in court rulings and other helpful trends. With natural language recognition, legal analytics could also be used together with automated contract generation and document assembly software to provide insights on how documents should be best drafted for a client. In Singapore, companies like Luminance, Lex Quanta and Pactly provide services in this area.

(H) Legal Business Consultancy Services

With the advent of numerous legal technology solutions, legal business consultancy services assist law firms and consumers of legal services in understanding and strategising the procurement of legal technology solutions. Some consultancy services also offer advice to in-house counsel regarding tools that assist in compliance management and workflow-monitoring.

In Singapore, KorumLegal and FirstCounsel mainly target SMEs in incorporating legal tech and providing legal advice. BiziBody Solutions advises primarily new law firms on the incorporation of the firm and the adoption of technology.

(I) Marketplace for legal services

Sometimes called the “Uber” of the legal sector, marketplaces for legal services connect potential clients with lawyers through an app or an online portal. In so doing, these marketplaces streamline the process of finding a suitable lawyer.

Such marketplaces often provide a searchable list of available and suitable lawyers. The client simply selects the preferred lawyer. The marketplace then acts as a middleman to connect the client with the lawyer. Some marketplaces also offer video conferencing solutions, providing even greater convenience to the lawyer and potential client. Examples of online legal services marketplaces in Singapore include Asia Law Network, Sleek, myLawyer and EasyLaw.

(J) Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) Platforms

In general, most ODR platforms cover mediation and arbitration service. Some platforms even offer a hybrid “med-arb” (mediation-arbitration) model of dispute resolution.

A typical model for the process of online mediation starts when an e-mail is sent to the parties containing the basic information on proceedings. The parties can send the mediator with the relevant documents electronically through the platform. The mediator can then convene virtual meetings, either between the mediator and each party, or simultaneously with all parties together. When the parties reach a settlement, the settlement agreement can then be signed electronically on the platform. In this regard, ODR platforms provide enhanced flexibility, given that parties are able to meet and communicate whenever and wherever is convenient for them. This convenience is particularly significant where parties are overseas and separated by multiple time zones.

Today, there is a growing number of ODR platforms globally. Many ODR platforms have been introduced in the Netherlands for small-claims procedures and legal-advice systems. A current market leader in ODR is Modria, which is currently partnering eBay, amongst others. It offers both mediation and arbitration, with customisable services provided in a modular manner. Singapore’s local courts have also been actively exploring the ODR space, with the Small Claims Tribunal and the Community Disputes Resolution Tribunal allowing litigants to commence cases entirely online. E-Litigation, the successor to the EFS (mentioned above), is also an ODR system that judges and lawyers to upload and access court documents online.

One interesting and related question would be whether the Singapore Judiciary would venture further and embrace the new technologies of AI and machine learning in dispute resolution. In Menon CJ’s Mass Call 2019 Address, he alluded to two examples of courts around the world potentially using machine learning in their reasoning processes: the Federal Court of Australia’s tool to help parties divide assets and liabilities following divorce, and the Estonian Ministry of Justice’s proposed system which can adjudicate small claims without human intervention. It remains to be seen whether the Singapore Courts would do the same.

(K) Smart Contracts

There are numerous applications of smart contracts in different industries globally, such as real estate, insurance, and simplified contract generation services. The main advantage of smart contracts is that it leverages on blockchain technology (see preceding section), which means that the middle man is removed from the deal such that more nuanced processes can be automated. For instance, in the real estate industry, smart contracts allows overseas buyers to interact with domestic sellers and even legally purchase and sell properties when they are not even situated in the country itself.

Smart contracts also have the potential to:

- Function as ‘multi-signature’ accounts, so that funds are spent only when a required percentage of people agree.

- Provide utility to other contracts (similar to how a software library works).

- Store information about an application, such as domain registration information or membership records.

Conclusion: Outlook of the legal technology sector in the next 5 years

As seen from the preceding sections, a quick review of the legal tech revolution in Singapore will show that it has gone through three main stages so far: (a) growing awareness about the impact of technology on practice, (b) increasing support and adoption of legal technology solutions, and (c) the generation of ground-up initiatives for legal tech adoption.

As we have done in 2018, we continue to take the view that the next stage of legal technology will be a phase of consolidation. In this phase, the industry is likely to see the need to collectively review the progress of the adoption of technology, reassess the extent to which legal technology solutions have transformed legal practice, and consider new approaches that will truly simplify and transform legal work (perhaps, for example, to combine multiple technology solutions together in one streamlined package). Along this vein, there may also be more mergers and acquisitions of legal tech companies – recent acquisitions include R&TT’s acquisition of e-discovery firm Legal Comet, and Asia Law Network’s acquisition of Regall.

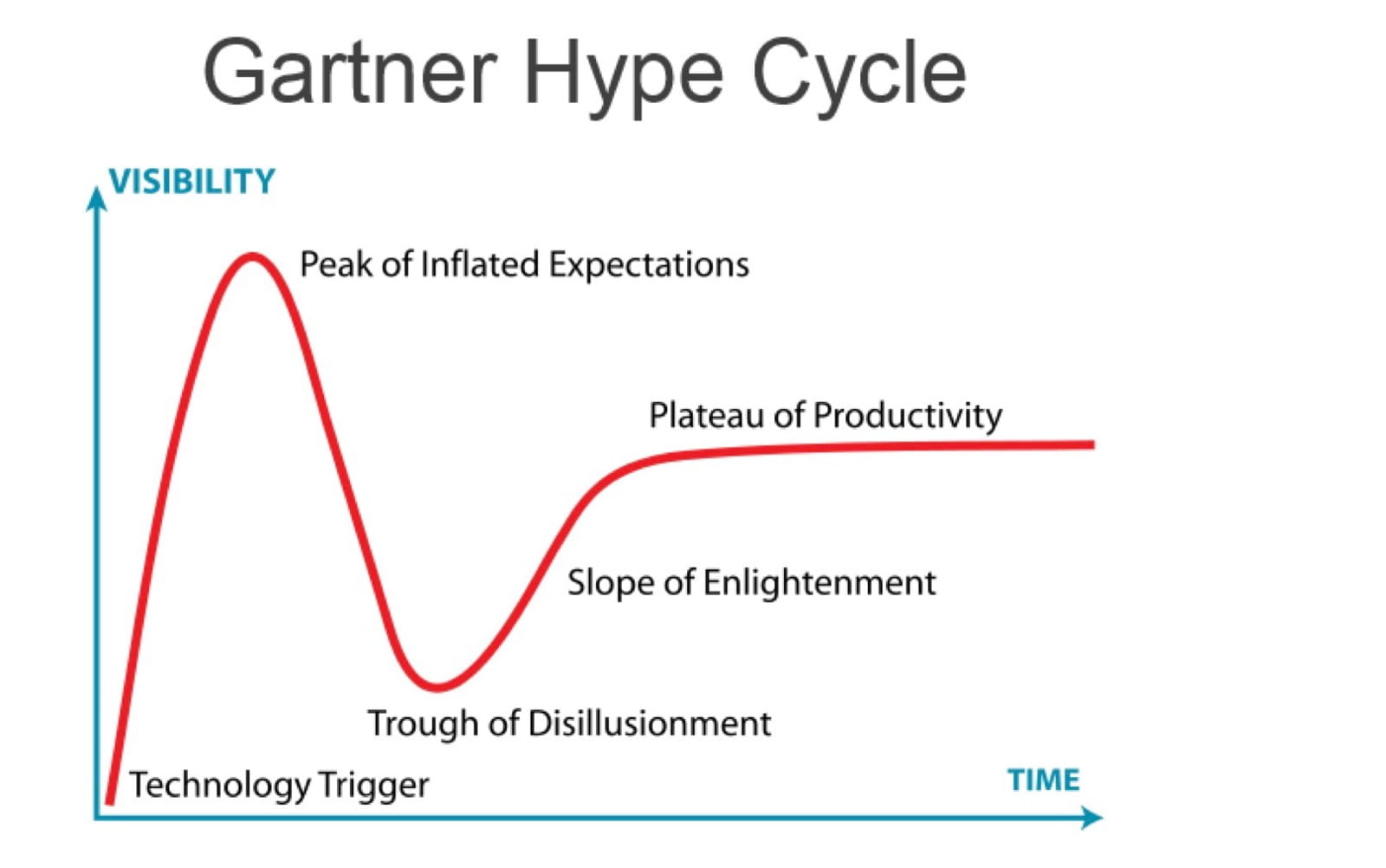

Our assessment of the next stage of the development of the legal technology sector is based on the Gartner Hype Cycle on technologies (see picture below). According to Gartner, an IT consultancy company, there is a discernable pattern in the life cycle of any technology, from conception, to maturity, and widespread adoption. In the case of Singapore’s legal tech sector, it is arguable that we are past the stage of initial excitement as the legal technology industry proceeds into a more mature stage. Indeed, as seen from public statements and speeches, there are signs that the industry is recognising the need to take stock of what is happening.

We are confident, however, that the legal technology industry will emerge from this phase of consolidation to see widespread adoption by law firms and consumers of legal services. This is because the fundamental realities of the legal market remain the same: that the legal services market is one that is ripe for disruption. In this regard, the Law Society of England and Wales’ predictions for the state of the UK legal market in respect of technology in 2020 paint a picture of an increasingly disrupted legal market in the coming years:

- An increase in the pace of technological change across all parts of society;

- An increase in the role and importance of technology in the delivery of legal services, including the ability to standardise or automate basic and process-driven legal services;

- Growing sophistication in the use of machines to read contracts – with potential on the horizon for machines to render judgment on formulaic cases;

- An overall increase in the amount of data and information exchanged online relating to legal cases and clients, requiring greater reliance on IT infrastructure and cyber security; and

- Greater expectations by clients regarding increased speed of services, and the ability to communicate and transact via mobile devices.

At this juncture, we wish to sound a note of caution that humans have traditionally been poor at predicting the future, and that unexpected changes could accelerate or entirely derail the broad forecast above. Nevertheless, it would be timely to recall the words of Bill Gates, written in his book, The Road Ahead, in 1996:

We always overestimate the change that will occur in the next two years and underestimate the change that will occur in the next ten. Don’t let yourself be lulled into inaction.

Bill Gates, The Road Ahead, 1996

In our view, there will be a “hockey-stick” moment where the rate of legal technology adoption increases exponentially – and the right question to ask should not be be when, but whether we will have sufficiently prepared ourselves for the disruption when it comes.

It remains to say that we good-naturedly challenge all of our readers to be so prepared when it does.

LawTech.Asia

Amelia Chew, Jennifer Lim Wei Zhen, Josh Lee Kok Thong, Tristan Koh (October 2018, 1st edition)

Utsav Rakshit, Tristan Koh, Cai Xiaohan (September 2019, 2nd edition)

The views expressed in the article above do not represent the position of any particular organisation or initiative, and are entirely the authors’ own.