Written by Tomoe Suzuki (Associate Author) | Mentored by Amelia Chew | Reviewed by Paul Neo

LawTech.Asia is proud to conclude the second run of its Associate Author (Winter 2019) Programme. The aim of the Associate Authorship Programme is to develop the knowledge and exposure of student writers in the domains of law and technology, while providing them with mentorship from LawTech.Asia’s writers and tailored guidance from a well-respected industry mentor.

In partnership with the National University of Singapore’s alt+law and Singapore Management University’s Legal Innovation and Technology Club, five students were selected as Associate Authors. This piece by Tomoe Suzuki, reviewed by industry reviewer Paul Neo (Chief Operating Officer, Singapore Academy of Law), marks the third thought piece in this series. It examines the rise of blockchain-based crowdsourced arbitration platforms.

Introduction

An earlier piece on “A brief analysis of the legal validity of smart contracts in Singapore” (“A Brief Analysis”) by Louis Lau on LawTech.Asia has explored the issues surrounding the adoption of smart contacts in terms of validity. This piece seeks to build on the aforementioned piece and add on to readers’ understanding of issues that arise in the implementation of these contracts and solutions that have arisen.

In particular, this article will compare various dispute resolution methods such as court-based litigation, mediation, arbitration (administered by arbitral institutions) to blockchain-based crowdsourced arbitration platforms (“BCAPs”) that have emerged in recent years. This piece will also provide a relatively abstract overview of how BCAPs work, the use cases they may be suited for, and highlight some of the challenges faced in increasing the adoption of smart contracts and BCAPs.

Smart contracts – local context and use cases

Borrowing Clack, Bakshi and Braine’s definition, a smart contract is an automatable and enforceable agreement – automatable by computer, though some parts may require human input and control, and enforceable either by legal enforcement of rights and obligations or via tamper-proof execution of computer code.[1] Smart contracts have the potential to lower the cost of transacting by reducing intermediaries (e.g. escrow services), and increase the speed and accuracy of transactions.

There are a variety of use cases for smart contracts, especially in the areas of trade clearing and settlement and supply chain documentation,[2] which are often hampered by the time taken to physically transfer documents. In Singapore, the adoption of blockchain and distributed ledger technology — essentially the foundational technologies that smart contracts operate upon [1] [2] — has been explored with much enthusiasm by larger institutional and commercial stakeholders through initiatives such as Project Ubin, a collaborative project between the Monetary Authority of Singapore and the financial industry.[3]

The starting point of this article is that all contracts are incomplete in the sense that it is not possible to provide for every possible contingency. If so, what occurs when disputes arise, and how suitable are existing dispute resolution mechanisms (e.g. litigation) for resolving smart contract disputes? What other tools are at our disposal to resolve disputes for smart contracts, and how do they operate?

Suitability of existing dispute resolution mechanisms

The availability and suitability of dispute resolution mechanisms influences the nature (e.g. use cases and user demographics) and extent of smart contract adoption. This article argues that existing dispute resolution mechanisms such as litigation and arbitration administered by arbitral institutions may pose barriers to the adoption of smart contracts by smaller businesses and individuals, due to the significant financial and time costs incurred in the process of resolving disputes. The costs of existing court-based litigation and arbitration are more easily borne by institutional and large commercial players who take on and afford greater risk in adopting new technologies.

General constraints: Time, money, jurisdiction

Court-based litigation and arbitration administered by arbitral institutions bear some similar characteristics:

- Proceedings are synchronous. All parties privy to the dispute must be present for the dispute resolution process to move forward;[4]

- They are often conducted face-to-face; and

- Bound by geographically determined jurisdiction.

The amount of time and money a claimant is willing to spend on the dispute resolution process is typically proportionate to that of the quantum disputed. In the interest of maximising access to justice (i.e.people with valid claims receive what they deserve) there is a need to develop dispute resolution mechanisms that minimise the time and money required for a dispute to be resolved. Otherwise, deserving claims may fall through the cracks simply because the cost of resolving the dispute is not justified by the quantum disputed.

Civil proceedings are also premised on the courts having jurisdiction, which may be difficult and costly to establish in cross-border agreements which do not provide for governing law or jurisdiction.[3] [4] Given the cost of conducting court proceedings, some claimants may not have the resources to apply for leave, to argue that there is a specific condition establishing Singapore as the natural forum for the dispute and a serious issue to be tried on the merits, and then serve the originating process on defendants outside of Singapore.

Issues faced with conventional arbitration

Where courts may not be a suitable avenue for dispute resolution, arbitration may be a viable alternative. In Singapore, arbitration is governed by both the Arbitration Act (“AA”)[5] and the International Arbitration Act (“IAA”).[6]

The Singapore International Arbitration Centre (“SIAC”) is the only international arbitration institution in Singapore. However, arbitration administered by the SIAC may sometimes not be feasible due to cost concerns. The Schedule Of Fees (effective as of 1 August 2014) published by the SIAC provides for a non-refundable case filing fee of SGD2,000 for Overseas Parties and SGD2,140 for Singapore Parties, in addition to an administration fee of SGD3,800 for sums in dispute of up to SGD50,000. The implication is that it makes little sense to pursue claims with a quantum of under SGD5,800. Note that SGD5,800 is a lower limit for costs, given that these costs are incurred before the Tribunal’s expenses and usage of facilities/support services are even considered. For a substantial number ofindividuals’ claims, SIAC-administered arbitration may therefore not be a cost-efficient solution.

BCAPs as a potential solution

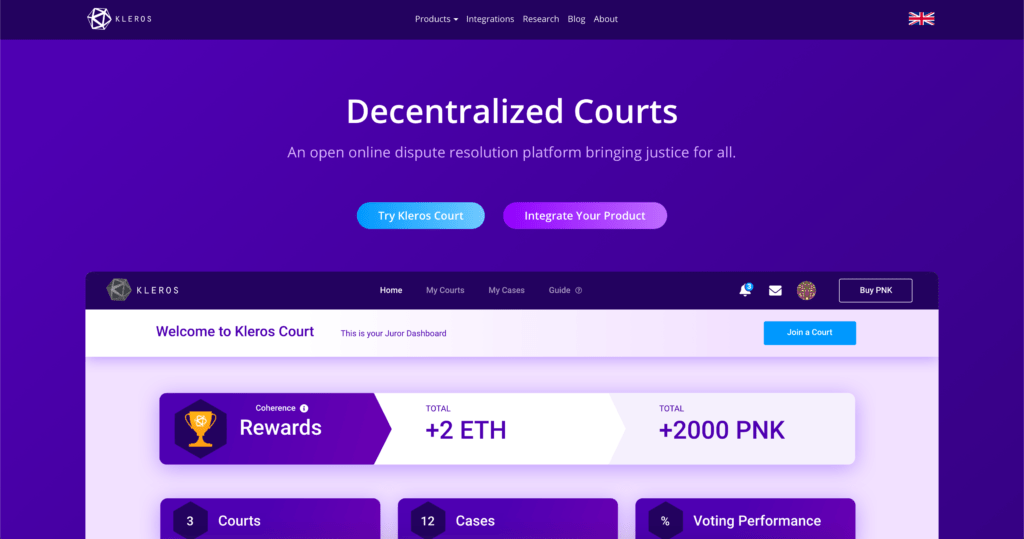

BCAPs can lower the barriers that individuals and smaller businesses face in adopting smart contracts by providing a more affordable method of resolving disputes compared to courts and arbitral institutions. The BCAPs that will be explored in this article are Kleros,[7] Jur,[8] and Aragon Court.[9]. The main draw of these platforms is that it allows parties to outsource decision-making in disputes to jurors who decide on them. BCAPs also avoid issues often faced in enforcement, given that payouts to parties are automatically executed when a decision is reached.

E-commerce, as an area that has not been explored as extensively in Singapore as fintech, could stand to benefit from BCAPs. From Mr Laurence Zhang (Director of Technology at the Institute of Blockchain Singapore; Kleros Ambassador)’s perspective, e-commerce is a good use case given its international nature, where our lives depend on trading internationally where dispute costs in terms of money and time can be prohibitive. Dispute resolution can be outsourced to BCAPs, hich would allow e-commerce platforms to save on the costs of managing an internal dispute resolution department.

How BCAPs generally work

Consent – arbitration is an opt-in system

Similar to arbitration administered by arbitral institutions, blockchain-based crowdsourced arbitration upholds the notion of party autonomy. In order for disputes to be arbitrated on BCAPs, the smart contracts in question must have an arbitration clause that designates the platform as the arbitrator.[10][11] The key difference between conventional employment agreements and their smart contract equivalent is that for the former, an arbitration clause can be independent from the main agreement, but in the context of smart contracts, they would need to be conditionally programmed to activate and commence the arbitration process upon the satisfaction of a certain event/condition.[12]

Proof of stake – selecting arbitrators

Each platform has their own token[13] (Kleros uses “PNK”; Jur uses “ANJ”; Aragon uses “ANT”), which we can think of as somewhat similar to casino chips. Users have an economic interest in serving as jurors by collecting arbitration fees in exchange for their work. The process of serving as an arbitrator is self-selecting: hopeful arbitrators stake their tokens, where the probability of being drawn as an arbitrator in a given dispute is proportionate to the amount that they stake.

The practice of staking tokens serves two important functions:

- Preventing Sybil Attacks”[14], where malicious parties can create a high number of addresses to maximise their chances of being drawn randomly, and hence control the system;

- Supporting the platform’s incentive system which promotes consensus, by making minority voters pay part of their stake to majority voters who are deemed to have voted coherently. This will be discussed in the section below.

Hostile takeovers where an individual or a group controls the outcome of adjudication by acquiring a 51% majority position of the token are unlikely given the potential prohibitive cost of acquiring 51% of all tokens may exceed the tokens’ initial value. Additionally, the existence of appeals mitigates concerns about bribery to a certain extent, given that attackers must keep bribing larger and larger juries all the way up to the General Court, in Kleros’ case.[15] Voting mechanisms can also play a role in preventing takeovers: in Jur’s case, if an unusually high number of votes are received right before a decision is due, voting is automatically extended.[16]

Schelling points – rewarding consensus

Jurors get to collect arbitration fees based on whether they vote for the option that the majority eventually chooses. In the event that they do not, the tokens that minority jurors initially staked (to become a juror) are taken away andawarded to majority jurors.

This incentive system is premised on Schelling points (a.k.a focal points) — a game theory concept introduced by Thomas Schelling — which suggests that in the absence of communication, there are certain solutions to problems that people tend to converge on, based on what they expect others to expect them to do[17]. Crowdsourced arbitration operates on the assumption that the majority view is correct – something that perhaps may not be correct where justice is concerned, but is adopted as a matter of practicality nonetheless.

Applying Schelling points to the adjudication context, we assume that there is a verdict that will stand out to others for some reason, and that the verdict’s notability will be picked up on by others and eventually lead to jurors voting for that decision.

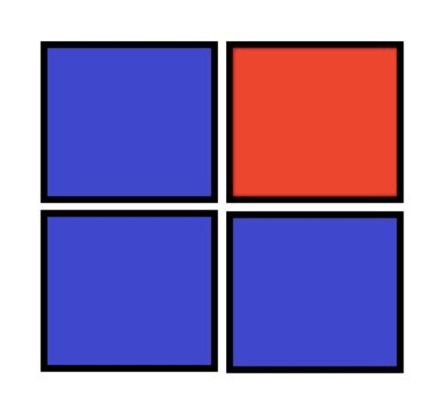

Consider the following scenario[18] where two people are told that they will receive some money if they select the same square without communicating with each other.

Given that the players know nothing about each other besides the fact that they both want to win a prize (get tokens), the two players will likely choose the red square. However, the red square, like any given verdict, is not a better square just because it is red, but because it is the most notable, for whatever reason – for colour, or perhaps for aligning with commonly held ideas of fairness. Technically, any verdict works as long as jurors choose the same verdict, just as any of the squares above would work as long as both players choose it. In a sense, arbitration premised on Schelling points assumes that there is a sufficiently common understanding of justice that allows jurors to assess and anticipate what other jurors find fair in a given case.[19]

The implementation of voting systems differs across platforms, even if they share a similar philosophical underpinnings. For Kleros’ case, jurors evaluate evidence and vote for a verdict, where their votes are not visible to other jurors or the parties in the dispute. This is meant to prevent the vote of a juror from influencing others.[20] On the other hand, votes on Jur are visible throughout the decision-making process[21] as they reward those who vote soon enough such that their vote is required to create or maintain the majority. The visibility of votes exerts pressure on jurors to analyse disputes and vote before others vote (otherwise, their vote is unnecessary for the creation of a majority, and they do not stand to gain) – this ultimately depends on how far one prioritises efficiency, and what factors jurors ought to be allowed to take into account when making their decisions.

Enforcement

Arbitration conducted by arbitral institutions is generally faster, but more expensive than national judicial systems. They are also not exempt from the time and monetary costs required to enforce awards. Blockchain-based crowdsourced arbitration presents a more affordable form of arbitration that the masses (including freelancers) are more likely to be able to access. Jur’s Open Layer envisions quick resolution (within 24 hours) of small value disputes (up to USD500) that would otherwise go unresolved, where there are few ways of resolving international disputes over smaller sums. While these sums are individually small, they aggregate to become a significant problem that ought to be addressed, for it entails “friction and inefficiency that stifles productivity and cooperation”.[22]

One of the reasons for blockchain-based crowdsourced arbitration platforms’ relative affordability is the fact that awards are often automatically enforced, and do not require the intervention of third parties (judicial or otherwise) to enforce them.[23] For instance, when parties opt in to designate Kleros to arbitrate their smart contracts, contracts will specify options for jurors to vote on, and specify the behaviour of the contract after a dispute is ruled on for various possible outcomes. In an example given in Kleros’ White Paper, that may include transferring funds to one of the parties’ addresses, or to extend the amount of time that one party has to perform their obligation (e.g. complete a website).[24] These actions can be executed without human intervention, and hence avoid the problems typically associated with enforcement in arbitration.

Conclusion

Given the rise of the gig economy, greater receptivity towards remote work and freelancing combined with new methods of contracting such as smart contracts, blockchain-based crowdsourced arbitration platforms can promote economic activity by providing a decentralised, self-enforcing way to resolve high volumes of potentially international disputes with lower quantum that may not be able to be resolved through traditional litigation and arbitration. As existing arbitral and judicial systems work to provide greater access through virtual hearings and asynchronous proceedings (e.g. documents-only trials) and limit the extent that unprecedented events (threaten to disrupt their ability to deliver justice, these platforms provide a viable alternative for parties whose disputes may otherwise go unresolved, or delayed for too long.

However, mass adoption of blockchain-based crowdsourced arbitration platforms may be hindered at the moment given that smart contracts (that these platforms can then arbitrate) may require a degree of technical knowhow to create and implement. Barriers to adoption can be reduced by abstracting the creation of smart contracts from programming to allow more people to make and edit smart contracts. For instance, Jur is currently working on Jur Editor, an editor that will allow users to easily create smart contracts with ready-made templates and a drag-and-drop interface.[25] The mass adoption of these platforms may be more viable as the general population becomes more comfortable with the sale and purchase of cryptocurrencies, given the introduction of the Payment Services Act which provides for the licensing of crypto platforms.

With regard to blockchain-based crowdsourced arbitration platforms themselves, platforms ought to be alive to the tradeoffs between robustness and efficiency – in endeavouring to make their protocols as robust so as to avoid the potential overturning of awards, they must also consider that they may risk replicating the legacy court systems that they operate in parallel with, and compromise the efficiency and cost-effectiveness that draws users to them.

[1] Clack, Bakshi and Brain, “Smart Contract Templates: foundations, design landscape and research directions” (2 August 2016) online: <https://arxiv.org/abs/1608.00771> . This definition has been adopted as it is flexible to the extent that a smart contract implementation can be fully implemented by computer code, or instead combine aspects of traditional contracts and computer code, as pointed out in “Are smart contracts contracts?” (Clifford Chance, 1 August 2017) online: <https://talkingtech.cliffordchance.com/en/emerging-technologies/smart-contracts/are-smart-contracts-contracts.html>. This corresponds to A Brief Analysis’ taxonomy of the Solely Code Model, Internal Model and External Model. Some people use “smart contracts” and “smart legal contracts” to distinguish between source code and digital versions of legal contracts where part or all of the agreement is executed algorithmically . See Herbert Smith Freehills, “Inside Arbitration: Smart contracts versus smart (and) legal contracts: Understanding the distinction and the impact of smart legal contracts on dispute resolution” (28 February 2020) online: <https://www.herbertsmithfreehills.com/latest-thinking/inside-arbitration-smart-contracts-versus-smart-and-legal-contracts-understanding>

[2] Deloitte, “CFO Insights: Getting smart about smart contracts” (June 2016) online: <https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/tr/Documents/finance/cfo-insights-getting-smart-contracts.pdf>

[3] Monetary Authority of Singapore, “Project Ubin: Central Bank Digital Money using Distributed Ledger Technology” online: <https://www.mas.gov.sg/schemes-and-initiatives/Project-Ubin>

[4] Richard Susskind, Online Courts and the Future of Justice (Oxford University Press. 2019) at p.60

[5] Arbitration Act (Cap 10, 2002 Rev Ed Sing) [“AA’]

[6] International Arbitration Act (Cap 143A, 2002 Rev Ed Sing) [“IAA”]

[7] Kleros, online: <https://kleros.io/>

[8] Jur, online: <https://jur.io/>

[9] Aragon Court, online: <https://anj.aragon.org/>

[10] Kleros White Paper, online: <https://kleros.io/whitepaper_en.pdf> at p.3

[11] Jur Editor, online: <https://jur.io/products/jur-editor/>. Jur has a product, Jur Editor, which allows users to create smart legal contracts that add a dispute resolution system based on the 3 tiers of dispute resolution that Jur offers.

[12] Nevena Jevremović, “2018 In Review: Blockchain Technology and Arbitration” Kluwer Arbitration Blog (27 January 2019) online: <http://arbitrationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/2019/01/27/2018-in-review-blockchain-technology-and-arbitration/?doing_wp_cron=1594664662.0058119297027587890625>

[13] Tokens are not quite the same as cryptocurrencies (“coins”) – the former builds on their another coin’s ledger (e.g. Kleros is built on Ethereum) while the latter has their own ledger/method to keep track of transactions. For more, see Marco Cavicchioli, “The difference between Token and Cryptocurrency” Medium (1 August 2018) online: <https://medium.com/@marcocavicchioli/the-difference-between-token-and-cryptocurrency-9dca9126fbda>

[14] Wikipedia, online: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sybil_attack>; Aragon Court supra note 14; Kleros White Paper supra note 16 at p.4

[15] Kleros White Paper, supra note 16 at p.9

[16] Chris Connelly, “Jur Voting System 101 – Part II” Medium (21 September 2019) online: <https://medium.com/jur-io/https-medium-com-chris-30703-jur-voting-system-details-e86d36dbbb15>

[17] In Schelling’s own words, Schelling points are “focal point(s) for each person’s expectation of what the other expects him to expect to be expected to do”. Thomas Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict (Harvard University Press, 1981) at p.57.

[18] Wikipedia, “Focal point (game theory)”, online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Focal_point_(game_theory). See section titled “In coordination game”.

[19] See Kleros White Paper, supra note 16 at p.8: “In Kleros, the Schelling Point is honesty and fairness.”

[20] Kleros White Paper, supra note 16 at p.6

[21] Jur, “Jur’s voting system 101 – Part 1” Medium (28 August 2018), online: <https://medium.com/jur-io/jur-voting-system-101-13081d12b351>

[22] Jur, “White Paper v.2.0.2” (July 2019) at p.41, online: <https://jur.io/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/jur-whitepaper-v.2.0.2.pdf>

[23] Ana Alexandre, “Decentralized Aragon Court Now Onboards Jurors to Settle Real Cases” CoinTelegraph (8 January 2020), online: <https://cointelegraph.com/news/decentralized-aragon-court-now-onboards-jurors-to-settle-real-cases>

[24] Kleros White Paper, supra note 16 at pp. 3-4

[25]Jur Editor, supra note 17

This piece was written as part of LawTech.Asia’s Associate Authorship Programme.