Written by Nigel Ang Teng Xiang | Edited by Josh Lee Kok Thong

We’re all law and tech scholars now, says every law and tech sceptic. That is only half-right. Law and technology is about law, but it is also about technology. This is not obvious in many so-called law and technology pieces which tend to focus exclusively on the law. No doubt this draws on what Judge Easterbrook famously said about three decades ago, to paraphrase: “lawyers will never fully understand tech so we might as well not try”.

In open defiance of this narrative, LawTech.Asia is proud to announce a collaboration with the Singapore Management University Yong Pung How School of Law’s LAW4032 Law and Technology class. This collaborative special series is a collection featuring selected essays from students of the class. Ranging across a broad range of technology law and policy topics, the collaboration is aimed at encouraging law students to think about where the law is and what it should be vis-a-vis technology.

This piece, written by Nigel Ang, explores current global regulatory measures surrounding loot boxes in video games. Question explored include: What is the problem with lootboxes that the proposed measures are attempting to solve? Who is, or should be liable for these problems? What is the next step for regulators and game developers? To answer these questions, focus will be on the interaction between both legal and non-legal regulatory measures taken, and the quirks and qualities of the technology each seeks to regulate. This includes the content of the games themselves, intermediary platforms that host such content such as app stores, and self-regulation from within the sphere of game development. The cultural and psychological phenomena that underpin the impetus for lootbox regulation will also be discussed.

Introduction

Lootboxes are a very popular monetization and progression subsystem in many video games. While the mechanics of each lootbox system varies from game to game, the basic premise of a lootbox involves players converting resources earned in-game into tries at a digital lottery to obtain in-game rewards. These rewards are often tiered into rarities, with the highest rarity tier of items having the lowest chance of being obtained per lottery attempt. Additional lootboxes can commonly be directly purchased with real money or earned in-game and requiring players to purchase “keys” with real money to unlock and receive their contents. Most commonly, lootboxes exist to encourage players purchase microtransactions built into the game.

Enjoying a meteoric rise in their implementation in the early 2010s, lootboxes have become ubiquitous and almost synonymous with the free-to-play/freemium model that has become the norm for many popular video games released in the last decade, especially those playable on mobile platforms such as iOS or Android. In recent years, lootboxes have transcended mobile titles and have controversially been featured in triple-A titles from major development studios, such as Electronic Arts’ Star Wars Battlefront and FIFA series. This has been described as part of the market shift towards the “games as a service”[1] revenue model, in other terms, continuous monetization of additional content and features after titles have been commercially released. Decried as being psychologically and financially exploitative and encouraging addictive behaviour, lootboxes have drawn no small measure of ire from legislators and discerning consumers alike. Despite controversy, lootboxes’ rapid proliferation and sheer volume of generated revenue speak far louder to their efficacy as a likely mainstay in the gaming industry for many years to come.

Why Regulate: The Psychology of Lootboxes

Before discussing the law and regulatory measures, important context on the motivations behind such movements should be discussed first. And to understand those motivations, we will briefly discuss what makes lootboxes work, and what makes them worthy of special regulation. At their simplest, lootboxes are a product that a company is trying to sell you, just like any other. However, this is accomplished through a complex and heavily market-tested interplay of not just psychological and marketing tactics, but how the technology at hand is creatively used by developers to advance those strategies.

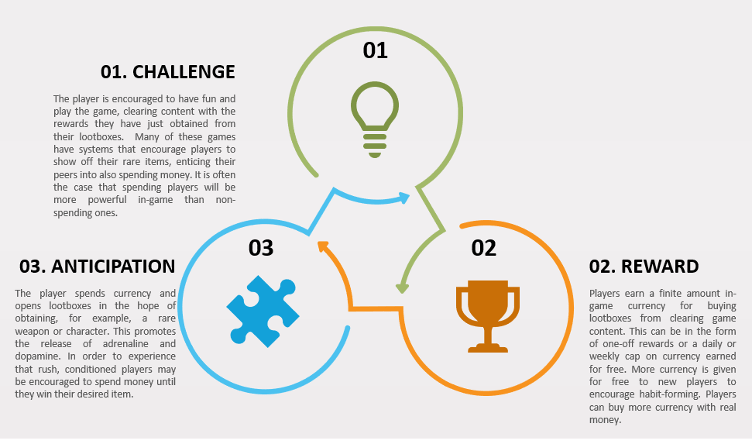

Many games that implement lootbox-style monetisation often try and form a “compulsion loop”,[2] or positive feedback loop when players first start playing the title. Dubbed by afficionados of lootboxes (and yes, they exist!) as the “honeymoon phase”, this is a period in which games tend to gift new players large amounts of lootboxes or the premium in-game currency used to buy lootboxes. The act of obtaining and opening lootboxes forms a habitual chain of activity that is aimed at releasing endorphins. Here is a simple diagram that illustrates this.

This is a tactic aimed at not just encouraging players to purchase microtransactions further down the line but is also aimed at maximising player retention. It should be noted that at every step of the cycle, the player-consumer has the opportunity and is encouraged to spend money to speed up the cycle to experience the rush of obtaining a rare item. To the “games as a service” model, the most desirable type of player is one who regularly plays, and regularly purchases microtransactions. Other tactics that are used in tandem with this basic feedback loop and made available through the unique technology and platform of a game include encouraging “FOMO” or the “fear of missing out”. This is accomplished through automated, instanced discount offers (for example, a “new player bundle” that can only be purchased within 48 hours of starting the game),[4] or by having certain items in the lootbox pool be removed after a promotion period ends with no indication on when, if at all, they will be available again. Purchasing lootboxes to strengthen one’s in-game capabilities can also be encouraged by carefully tailoring the difficulty curve of the game to require or favour high-rarity, lootbox-exclusive equipment, or characters.

Although anyone can partake in these games, the ethical issues with this model are at their starkest when minors become involved. Children are more psychologically impressionable and therefore more susceptible to compulsion loops like this one. They are also physiologically predisposed to having poorer impulse control and long-term decision making regarding their resources, which is why an age of majority and contractual liability exists. The incorporation of lootboxes into video games of franchises very popular with children (such as Square Enix’s Marvel’s Avengers[5] or the aforementioned Star Wars Battlefront) has thus sparked furious debate. Regulators and legislators alike have risen in an international movement in a bid to quash what many consider to be a new, powerful, and potentially dangerous form of video game addiction through means including amendment of laws and class-action lawsuits: all to be discussed shortly.

Statutory Bans: Comparisons to Gambling

The elephant in the room when discussing the statutory regulation of lootboxes is the question of whether the proffering of lootboxes constitutes gambling. It is not a controversial parallel, as many similarities can be drawn between the acts, both systems having invited the scorn and scrutiny of regulatory bodies for the dangers of addiction. While a connection between the practices has been suggested by regulators in the UK,[6] Belgium has taken steps to outright enshrine this comparison in law. The country has assimilated lootboxes as a form of gambling under their existing gambling regulation statute, the Federal Act of 7 May 1999 regarding games of chance, wagers, and protection of the players, also known as the Belgian Gaming Act.[7] It was through a report by the Belgian Gaming Commission, the regulatory body overseeing the Act, that lootboxes should be defined as a “stand-apart” game feature that represents a “game of chance” with a “stake”.[8] It should be noted that there was no amendment to the statute itself (and thus no statutory definition for a lootbox), and that this report simply offered confirmation that lootboxes were to be considered under the ambit of the Act’s powers.[9]

However, this reasoning is problematic. The conflation of lootboxes and gambling is an overly reductive generalization that conveniently smooths over the peculiarities and unique qualities that set lootboxes aside from gambling, not just as a platform for monetization but as a technology. It is because of these qualities that simply enacting a blanket ban in law, despite the strong message it sends, is simply not efficient, or have a real impact on the problem that it purports to solve. Perhaps this is a natural consequence of the Commission’s attempt to subsume lootboxes under a law that was not drafted with their inclusion in mind.

What stands out is the difficulty and inconsistency of enforcement of the Belgian law in its current state, and how their existing measures for dealing with illegal online gambling sites through the Act may not work as well for their blanket ban on lootboxes. Currently, the Commission operates a blacklist of illegal offshore gambling sites, but the same measures have not been implemented for games. With that said, many popular titles have pulled either pulled their games from Belgian stores (Fate/Grand Order and Arknights) or disabled the option to purchase lootboxes in-game with real money (Final Fantasy Brave Exvius and Apex Legends) to avoid the expensive gambling license fees they must now pay to operate within the country.

However, circumventing the former as a consumer is a simple matter of sideloading the application through installing a downloaded Android Package file or creating an out-of-region App Store account through a virtual private network. As for the latter, it is confusing from a public policy stance that the law still allows games featuring lootboxes to continue to operate with the caveat of disabling real-money purchases. Lootboxes can still be earned and opened without real-money purchases, and the addiction loop continues to be fed. Addicts can then resort to the measures described earlier to easily access a version of the game that allows microtransactions. In addition to this, the regulatory measures taken have been egregiously inconsistent. For example, the Playstation 4 port of popular lootbox social game Genshin Impact has been banned in the country, but the Android and iOS ports are completely playable without restriction to this day.[10] The Commission could have done better by framing the legal issues as consumer protection law as opposed to gambling regulation and prioritized raising awareness of the addictive nature of lootboxes. This is a much more realistic and forward-looking approach that actively protects those vulnerable to exploitation, especially given the prevalence of lootboxes in games is only likely to increase over time and outpace the law that seeks to regulate it.[11]

Intermediary Liability: Coffee v. Google and the Communications Decency Act

The Californian putative class-action lawsuit of Coffee v. Google[12] provides talking points on where liability should lie with objectionable app content, specifically the proffering of games containing lootboxes. The facts: the plaintiff Coffee, and their son, had downloaded and purchased almost $600 USD worth of lootboxes on two free-to-play Play Store titles. They alleged that lootboxes constitute “illegal slot machines or devices” under Californian law, and that Google was complicit in proffering these apps without screening them first, as Google takes a 30% cut of all microtransactions conducted through its Play Store platform. Google responded by arguing that it was immune from liability under s 230 of the Communications Decency Act (“CDA”).

Unfortunately, the case never turned to the question of whether lootboxes were illegal under Californian law, as Google was indeed deemed to be immune from liability under s 230 of the CDA. However, an important point was reinforced with regards to the interpretation of s 230: That the “publishing of apps” falls within the meaning of “publishing of speech” and affords the same protections to an intermediary under the CDA. This was first raised in a 2013 case[13] and serves as exemplary of the wide ambit of s 230, often criticized for “leaving victims of online abuse with no leverage against the site operators whose business models facilitate abuse”.[14] While some legal scholars advocate that the answer to s 230’s shortcomings is not imposing liability upon intermediaries,[15] it is unsatisfactory that this case and the CDA does not yet provide an answer as to accountability for lootboxes; a type of app content that has been conclusively proven harmful to a sizeable demographic. As takedown requests are presently directly submitted to the intermediary, the absence of a formal legal mechanism to regulate speech (and therefore apps) renders all takedowns entirely voluntary.[16]

The current state of affairs in the States troubling on both a legal and public policy standpoint. The current interpretation of s 230 in Coffee allows intermediary platforms to escape scrutiny and merit review of the content that they push out on the basis of upholding a poorly defined and excessively broad protection of speech. It is acknowledged, however, that doing the reverse and holding Google fully liable would produce not only a ceaseless torrent of vexatious lawsuits, but also a chilling effect and troublesome precedent for the innumerable stakeholder industries supporting themselves through Google’s framework. Given the courts’ attitude towards s 230, it would be unrealistic to expect any major legal developments or concessions in this area in the near future leaning towards stricter regulation for publishers of third-party app content, and thus, lootboxes.

If s 230 presents itself as an insurmountable wall, the only way forward is to not attempt to scale it in futility, but to walk around it. Instead of declarations of law, another equally effective method of holding both distributors and creators of these games accountable for their actions is spreading awareness of the harmful qualities of these mechanics inserted into the games they publish or produce. This arms the public with the knowledge that allows them to make wiser decisions for themselves as well as any vulnerable parties in their care. These measures would also shift public perception of the gaming industry and what is or isn’t acceptable to consumers. In fact, several countries outside the US and the western world at large have chosen to adopt this approach over legislative or judicial measures. It may come as a surprise to some readers that these very same countries are places where lootboxes are the most prolific and popular – and yet very little hard law is needed to cement a robust set of standard industry standards and moral duties for those seeking to monetise their games through lootboxes. The last case study of this paper will discuss the unique circumstances and measures taken by the country credited with pioneering and popularizing the video game lootbox as we know it: Japan.

Self-Regulation of Lootboxes: Internally Setting Industry Standards

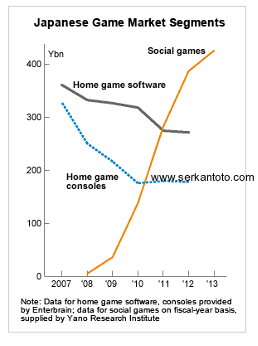

Japan is widely considered by the gaming community as the progenitor of the lootbox, having implemented the mechanic in online social games for far longer than the rest of the world. The term gacha, now a popular loanword in the West for lootboxes, is a Japanese onomatopoeia for the clunking of a capsule machine[17] as it dispenses its prize – one of the earliest forms of traditional lootbox mechanics. Social games played on the smartphone in Japan are a massive market that eclipses home console and PC gaming and had an approximate revenue of $USD 19.2 billion in the year 2018.[18]

Most of these games contain gacha, or lootbox mechanics, but it may come as a surprise that Japan’s massive lootbox economy is by and large self-regulated, and as mentioned, very little black-letter law restricting these lootboxes exists aside from a very specific exception. This exception, is known as complete gacha or compu-gacha, refers to a type of multi-level lootbox that requires players to obtain, or “complete” all prizes in a set to obtain a “Grand Prize”. This was condemned by the Japanese Consumer Affairs Agency in 2012, which considered this practice exploitative and banned it. Right before regulators could step in, market-dominating social game developers (Gree,DeNA, Mixi, CyberAgent, Dwango and NHN Japan) formed their own self-regulation council[20] and announced several undertakings that would eventually go on to shape the market:

- The disclosure of probabilities to obtain all items through lootboxes, so consumers understand the chances to win each prize,

- Strict regulation of secondary markets and real-money trading of game contents,

- Prohibition of complete gacha, and

- The formal creation of an internal industry regulatory committee involving social game operators, third party developers and consumer groups, including consumer consultation circles, dedicated to improving public awareness of how to safely enjoy social games, especially for young players.

There are many benefits to this approach. On the debate of tortious liability against self-regulation, in his well-known paper on the debate between liability and regulation,[21] Steven Shavell considers one of the determinants of assessing the social desirability of liability against regulation to be the difference in knowledge about a risky activity between a private party benefiting from the activity, and a regulatory authority. This problem is eliminated here, as the private parties are the regulatory authority. Another point Shavell makes that is relevant to lootboxes favoring regulation is the wide dispersal of generated harms. This allows offending parties to escape suit through the difficulty of a singular victim pursuing an action, or the failure to sue through the inability to attribute harm to the parties responsible for producing it, which is reminiscent of this paper’s previous discourse on s 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

What made this tacit arrangement between industry players only possible in Japan is a conflux of cultural and economic factors unlikely to be found in other countries. The sheer competitiveness of the social game industry in Japan forces new developers to conform with these standards lest they be labelled as predatory and exploitative, even in the absence of black-letter law mandating these practices. It is for the same reason that the danger of conflict of interest that arises from a regulatory body also being the financial beneficiary of the content it regulates is also practically non-existent, as these companies cannot afford to be seen as taking advantage of players and risking losing consumers’ trust.

A perfect example of this occurred 3 years after the formation of the council with Granblue Fantasy, one of the top lootbox social games managed by council member CyberAgent. Known overseas as “Monkeygate”,[22] this was a serious controversy where a Granblue Fantasy player had livestreamed himself purchasing 2276 tries, or USD $6065 before succeeding in winning his desired prize from a lootbox, once again throwing lootboxes into the limelight of Japanese mass media for months. CyberAgent immediately apologized and implemented a ceiling of 300 tries before a desired prize is guaranteed, a practice that has once again become the norm for most Japanese social games in the aftermath of Monkeygate. It is difficult to say that this response and level of earnest self-regulation would be replicable overseas given the lack of pressure from lower competitiveness and therefore lower public awareness of the harm of lootboxes. Japan nonetheless serves as an aspiration point of what can be achieved outside the confines of the law given proactivity on the part of both the public and developers.

Conclusion: What Comes Next? Thoughts on the Future of Lootboxes and Law

Gaming, like any emergent technology, is in a constant state of innovation and reinvention. And as is often the case, the law struggles to adopt a prophylactic approach to these rapid changes. Any competent developer that incorporates lootboxes as part of their game will learn from their predecessors’ strengths and failings when designing their monetisation model. This is a double-edged sword: Increased public awareness on the harmful qualities of lootboxes will invariably lead developers to implement measures to ameliorate those concerns, but in turn they will learn exactly what consumers are willing to tolerate before becoming disgruntled. It is a delicate balance that many have attempted to shift through various means: legislative bans, lawsuits, self-regulation, and perhaps more that this paper has not had the opportunity to discuss at length. None of these are perfect nor universally applicable but remain applaudable as valiant efforts made and a good start to address a concerning practice in a massive industry. To conclude, I would like to note with horror that as of 2021, certain social games already offering lootboxes have begun incorporating blockchain and cryptocurrency[23] as well as non-fungible tokens[24] into their monetization models. I await with equal trepidation as a consumer and enthusiast of games and excitement as someone with great interest in the surrounding law and look forward to writing all about new developments in this area as they arise.

This piece was published as part of LawTech.Asia’s collaboration with the LAW4032 Law and Technology module of the Singapore Management University’s Yong Pung How School of Law. The views articulated herein belong solely to the original author, and should not be attributed to LawTech.Asia or any other entity.

[1] Karina Arrambide, “Games as a service – the Model of microtransactions” [2018] https://medium.com/@hcigamesgroup/games-as-a-service-the-model-of-microtransactions-1a0e1e847119 (accessed 20 Nov 2021)

[2] John Hopson, “Behavioral Game Design” [2001] https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3085/behavioral_game_design.php?page=1 (accessed 20 Nov 2021)

[3] Graph produced using a template from www.presentationgo.com (Accessed 21st February 2022)

[4] Here is a real example of a “typical” new player microtransaction offer, from CyberAgent’s game Granblue Fantasy. https://gbf.wiki/Beginner%27s_Draw_Set (accessed 20 November 2021)

[5] Tomas Franzese, “Marvel’s Avengers Spider-Man Update Sneaks in a Controversial Mechanic” [2021] https://www.inverse.com/gaming/marvels-avengers-roadmap-spider-man-update-cosmetic-loot-boxes (accessed 1 December 2021)

[6] John Woodhouse, “Research Briefing: Loot boxes in video games” UK Parliament Library of Commons (2 August 2021) at p 6 – 8.

[7] Wet van 7 mei op de kansspelen, de weddenschappen, de kansspelinrichtingen en de bescherming van de spelers.

[8] Philippe Vlaemminck and Robbe Verbeke, “The Gambling Law Review: Belgium”, The Gambling Law Review (7 June 2021) at i.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Unknown author, “Genshin Impact is banned in Belgium due to lootboxes…but only in the PS4 version” https://samagame.com/00/en/genshin-impact-is-banned-in-belgium-due-to-loot-boxes-but-only-in-the-ps4-version/, (accessed 30 November 2021). As this source isn’t reliable, I took the liberty to confirm this myself with a Belgian acquaintance as well as attempting to download Genshin on Android through a Belgian VPN. Both these methods confirmed the veracity of this claim.

[11] David Zendle, Nick Balou and Rachel Meyer, “The changing face of desktop video game monetization: an exploration of trends in lootboxes, pay-to-win and cosmetic microtransactions in the most-played Steam games of 2010 -2019”, PsyArXiv Preprints 2020.

[12] Coffee v Google LLC [2021], Case No. 20-cv-03901-BLF.

[13] Evans v Hewlett-Packard Company [2013], WL 5594717 at *1.

[14] Danielle Keats Citron and Benjamin Wittes, “The Internet Will Not Break: Denying Bad Samaritans § 230 Immunity”, Fordham Law Review, Volume 86, (2017) at 401 and 404.

[15] Eric Goldman, “Why Section 230 is Better Than the First Amendment”, Notre Dame Law Review, Volume 95 (2019) at p 33 – 34.

[16] Jacquelyn E. Fradette, “Online Terms of Service: A Shield for First Amendment Scrutiny of Government Action”, Notre Dame Law Review, Volume 89 (2014) at p 967.

[17] For reference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gashapon (accessed 23 Nov 2021)

[18] Baker McKenzie, “Loot Boxes in Japan: Legal Analysis and Compu Gacha Explained”, Lexology (2018) https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=9207df10-a8a2-4f67-81c3-6a148a6100e2 (accessed 23 Nov 2021)

[19] Image source: https://www.serkantoto.com/2013/02/11/social-console-games-japan/ (accessed 23 November 2021)

[20] Serkan Toto, “Six Japanese Social Gaming Companies form Council to Self-Regulate Monetization [Social Games]” https://www.serkantoto.com/2012/03/24/japan-social-game-makers-self-regulation-council/ (accessed 23 November 2021)

[21]Steven Shavell, “Liability for Harm versus Regulation of Safety,” The Journal of Legal Studies (1984) 13, p 360 – 363.

[22] Ollie Barder, “Japanese Mobile Gaming Still Can’t Shake Off the Spectre of Exploitation”, Forbes (4 April 2016) https://www.forbes.com/sites/olliebarder/2016/04/04/japanese-mobile-gaming-still-cant-shake-off-the-spectre-of-exploitation/?sh=31a034085a27 (accessed 23 November 2021)

[23] See: https://bravefrontierheroes.com/ (accessed 1 December 2021)

[24] Danny Peterson, “A Mobile Game is Under Fire for Doing NFTs”, We’ve Got This Covered (10 November 2021) https://wegotthiscovered.com/gaming/a-mobile-game-is-under-fire-for-doing-nfts/ (accessed 1 December 2021)