Written by Alexis N. Chun

Last week we spoke about the status quo in law and how we at Legalese and the Computational Law Centre (CCLAW) at Singapore Management University are working together to make Computational Law a reality. This is part 2 of this 3-part series.

If you recall, we discussed the (natural) language problem of law and how perhaps a domain-specific language (DSL) for law might be the foundational technological innovation to fix it. Because a DSL gives “Law” (which term we use to collectively refer to statutes, regulations, contracts, guidelines, business process logic, rules, quasi-legal documentation, you name it) a common denominator, the disparate bits can now “talk” to each other. This is what makes “Law” computable and computational. And in our vision, this foundational technology gets us from pseudocode to real code. That’s what we suspect a contract wants to be when it grows up: a program. And the marvellous thing about programs is that Law can graduate from simply expressing syntax (i.e. words on a page, legalistic expressions) that are essentially pseudocode to semantics (i.e. what does it mean in an objective or clearly defined fashion), to pragmatics (i.e. what does it mean for me). Semantics and pragmatics are the traditional demesnes of lawyers; these are things you’d pay and ask for a lawyer’s advice on. But lawyers’ service of semantics and pragmatics may be too much like a priesthood (and too expensive) for most end users: go forth with this blessed document, but don’t break your back carving out the laundry list of assumptions, professional indemnities, and deciphering what exactly it means for you. Take faith. This just might not cut it anymore for the increasingly tech-savvy and knowledge-driven common man on the Clapham omnibus who reviews and background checks everything including their drivers, romantic dates, and restaurants.

So what’s slightly better (not perfect) than taking faith?

With a DSL as the foundational infrastructure for “Law”, you can apply the batteries of tools that computer scientists have at their disposal (which lawyers don’t even have names for) to “Law”.

We argue that this, though not perfect, is better. What computational law (for easy reference, let’s call it CLAW) does, is create the opportunity for services (e.g. bringing syntax to semantics to pragmatics) to be commoditised.

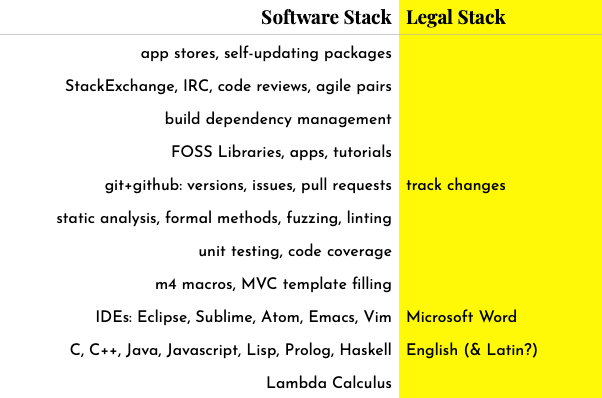

Let’s contrast what an average software stack looks like compared to its legal stack equivalent:

Sure it doesn’t look great now, because law predates software and has been playing catch-up for a very long time. But this also means that in every area that law currently pales in comparison with software, there is an opportunity that CLAW can innovate on.

How that CLAW future might look like

When the laws change, that’s like a software update. One can even make it a self-updating package with automatic notifications.

Documents depend on each other and you have to track all your obligations and dependencies to make sure they don’t conflict or create ambiguity? Meet dependency management! One can layer the development architecture modularly the way software development does today. Add to that, acceptance testing, which allows you to evaluate compliance with your specified rules.

How about static analysis? We could test, calculate, and model (mathematically, visually, textually, you name it!) the effects of a change to a system, without first implementing the change. Software code gets testing all the time prior to execution. Finding bugs at run time? That’s called litigation.

Unit and integration testing are also cool. We could unit test individual pieces of the codified Law or even modules of them together (e.g. a certain business process, guidelines) with controlled data, usage and operating procedures to determine if they are fit for purpose.

Not everyone needs to learn the DSL

Please don’t learn to code, unless you want to. I get asked the “gosh, do I need to learn how to code now?” question, a lot. Yes, as with law, the alarmist “shortage” issue often gets recklessly thrown about, but what they really mean is that there’s a shortage of senior or full-stack developers (this applies to lawyers as well) – and that’s usually not something a bootcamp or any 101 course can easily or quickly help transform you into.

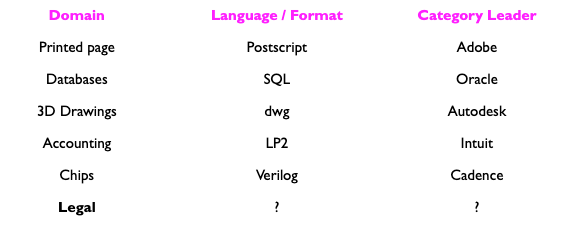

The good news is that you don’t need to learn the DSL to be part of the CLAW future. We’ve known about low-code platforms for awhile now. In fact, most of us are already using what are essentially, low-code platforms: spreadsheets and their formulas, Word documents with macros, photo editing apps & software. The DSL and CLAW act as foundational technologies on which applications, software, low-code platforms, can be built atop. Foundational technologies are often invisible to the end-user (you don’t need to know Postscript to use Adobe) and that’s a good thing.

Instagrammification of Law

I call this the Instagrammification of Law. We no longer need to learn about aperture, focal lengths, exposure, or colour theory to take good pictures with our phones anymore – we know and can see that we’ve got what we want by applying a filter, moving a slider, tapping on a screen. That’s the CLAW future I’m signing up for. With a DSL as the foundational technology for apps and software, functionalities can allow one to (this is non-exhaustive):

- see what the outcome looks like and tweak it to one’s liking prior to signing

- automatically generate the same document in different natural languages with the assurance that the base logic and outcomes remain the same

- import different applicable laws or regulations as libraries with a click of a button without having to manually update each provision

- run consistency checks with other documents one’s entered into

- integrate notification obligations with calendars and project tasks

That’s way too out there… is it though?

Let’s go back to the idea that today we’re still paying lawyers by the hour for manual labour (typing) and priesthood analysis. Now let’s look at what other professional domains have.

Accounting: Think of the last time you paid for someone to do your mental sums and set up manual accounting ledgers. Did you really do that or did you pay for someone to use accounting software and spreadsheets instead?

Photography. Think of the last time you paid for someone to take photos with an analog camera. Or did you pay someone who used a digital camera with post-production editing skills, or did you simply use your phone?

Architecture. Think of the last time you paid an architect to hand-draw blueprints and set out measurements. Or did you pay for an architect skilled in AutoCad software that inherently recognises object and structural relationships?

Graphic Design. Think of the last time you paid a designer to hand-draw on pen and paper. Or did you pay for a designer skilled in editing and creative software?

Law. Now, think of the last time you paid a lawyer to do all their thinking in their head and set it all down in Microsoft Word. The analysis is opaque, and because it’s not unified by software or technology, what you get might just depend on their workload for the day, whether they’re rushing off somewhere, or even simply, whether they’re on their first cup of coffee or sixth.

The idea that vertical innovation (recall Zero to One from earlier) happens in a professional domain via the invention of a domain specific language or format is a well-honed software tradition. I’ll save you the florid grandstanding with this:

Next week, in the final article in this series, we’ll talk about how such a transformation might happen, and where CLAW fits in with all the LegalTech flurry that we’ve been seeing.

Alexis N. Chun is Industry Director at the Computational Law Centre (CCLAW) of the Singapore Management University She is also the co-founder of Legalese.com. This article has been re-published with consent from CCLAW.

Acknowledgement: This research / project is supported by the National Research Foundation, Singapore under its Industry Alignment Fund – Pre-positioning (IAF-PP) Funding Initiative. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the views of National Research Foundation, Singapore.