Written by Delvine Tan Hui Tien | Edited by Josh Lee Kok Thong

LawTech.Asia is proud to collaborate with the Singapore Management University Yong Pung How School of Law’s LAW4060 AI Law, Policy and Ethics class. This collaborative special series is a collection featuring selected essays from students of the class. For the class’ final assessment, students were asked to choose from a range of practice-focused topics, such as writing a law reform paper on an AI-related topic, analysing jurisdictional approaches to AI regulation, or discussing whether such a thing as “AI law” existed. The collaboration is aimed at encouraging law students to analyse issues using the analytical frames taught in class, and apply them in practical scenarios combining law and policy.

This piece, written by Delvine Tan Hui Tien, explores and analyses Japan’s approach to AI regulation. It examines the principles, reasons and examples behind Japan’s approach to traditional AI and generative AI.

Introduction

Three elements are needed to take advantage of artificial intelligence (“AI”): entrepreneurs to bring about breakthrough innovations, companies to provide financial resources and infrastructure, and government policies that provide the appropriate environment.[1] Japan is a prime example of this synergy. This economic powerhouse believes that industry and government should work together as partners, rather than viewing each other as adversaries, resulting in the country’s many breakthroughs in innovation.[2]

Japan is actively involved in developing and promoting the growth of AI, recognising its transformative potential for various aspects of society, industry, and innovation. The Japanese approach to AI is characterized by a combination of technological advancements, research initiatives, and a focus on incorporating AI into different sectors of the economy.[3] One distinctive aspect of Japan’s engagement with AI is its long-standing history and strong foundation in robotics and automation, which expertise in this area has naturally extended to AI.[4]

This paper explores and analyses Japan’s approach to AI regulation. It first focuses on Japan’s approach to traditional AI, followed by generative AI.

Japan’s AI regulatory landscape

There are currently no legislation specific to AI, neither are there any regulation that governs AI in Japan.[5] This relatively hands-off approach reflects Japan’s inclination towards soft rules governing the use of AI, with its aim to harness AI’s positive impact on society rather than stifling innovation with excessive rules.[6] Japan believes in a lax regulatory environment that encourages developing and applying AI technologies across various sectors without imposing stringent sector-specific mandates.[7]

There are several reasons for this approach. Principally, the nation intends to use AI to boost its economic growth, expand its position as a global leader in advanced chips, and position itself as a global leader in AI.[8] A report by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (“METI“) shared that the country deemed it unnecessary for legally binding horizontal requirements for AI systems at the moment. The rationale being it is difficult for regulations to keep up with developments in AI, and a prescriptive, static, detailed regulation could hinder the growth of AI innovation. METI concluded that the government should allow companies to have their own AI governance while providing a flexible guidance to support or guide their efforts.[9]

This is in line with Japan’s emphasis on innovation and technological advancement, particularly in sectors like robotics, AI, and automation. A “hands-off” regulatory approach allows for greater freedom and flexibility for companies and researchers to experiment, innovate, and develop AI technologies without being burdened by overly prescriptive or restrictive regulations.[10] For example, AI could help cope with Japan’s ageing population and population decline that is causing a labour shortage in its economy. It could also stimulate demand for advanced chips that government-backed venture, Rapidus, plans to manufacture as part of an industrial policy aimed at regaining Japan’s lost lead in technology.[11]

Further, Japan has a cultural inclination towards consensus-building, gradual change, and harmonious relationships between government, industry, and society. Soft law instruments, such as guidelines, principles, and voluntary standards, align well with Japan’s preference for flexibility, cooperation, and non-confrontational approaches to governance.[12]

Japan’s approach to traditional AI

Japan’s AI initiatives are built on the concept that no single company or nation can supply all the answers needed in this fast-changing technology. Therefore, key parts of the government’s policies are to work with countries, corporations and entrepreneurs from around the world to bring this new industrial revolution into reality.[13] It has been noted that “Japanese government is moving really fast… in terms of regulation compliance or in terms of research funding”.[14] This is reflected in the many initiatives that comprises Japan’s AI policy approach. Inter alia, some notable ones are the Japan AI Strategy 2022, Governance Innovation (2020 and 2021), AI Governance in Japan Ver 1.1.

Before delving into the various AI initiatives, it is crucial to understand that Japan is striving towards a vision of its future society, known as Society 5.0. It was first proposed as “a human-centred society in which economic development and the resolution of social issues are compatible with each other through a highly integrated system of cyberspace and physical space (“CPS”)”.[15] It is a super-smart society where technologies such as big data, Internet of Things (IoT), AI, and robots fuse into every industry and across all social segments.[16]

“Happiness” is the ultimate goal of Society 5.0, with liberty as the goal of governance in Society 5.0.[17] The Cabinet Office describes Society 5.0 as an initiative aimed at ensuring safety, security, comfort, and health for all individuals, facilitating the pursuit of preferred lifestyles.[18] This background would help us to better understand the policy considerations driving Japan’s AI initiatives.

Japan AI Strategy 2022

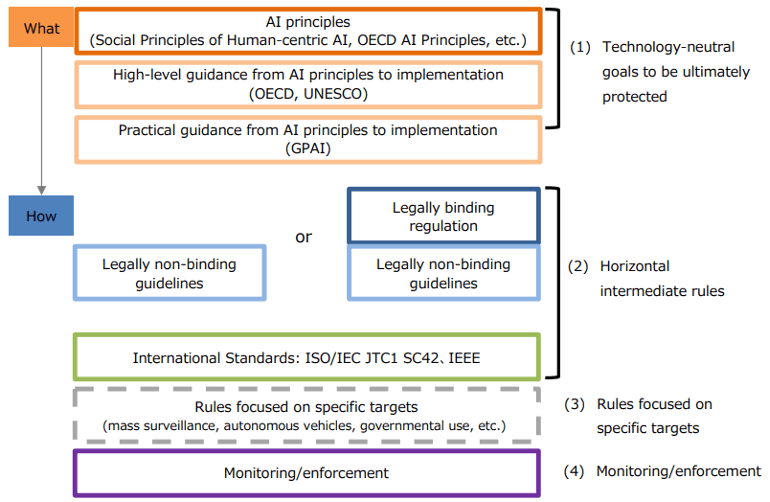

In 2019, the Japanese government published the Social Principles of Human-Centric AI (“Social Principles”) as guiding principles for implementing AI in society. The Social Principles set forth three basic philosophies: human dignity, diversity and inclusion, and sustainability. The goal is to realise these social principles through AI instead of restricting the use of AI to protect these principles. This corresponds to the structure of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (“OECD”) AI Principles, whose first principle is to achieve “inclusive growth, sustainable development, and well-being” through AI.[19]

Japan’s AI regulatory policy is based on these Social Principles, which sets forth seven principles surrounding AI: (1) human-centric; (2) education/literacy; (3) privacy protection; (4) ensuring security; (5) fair competition; (6) fairness, accountability, and transparency; and (7) innovation. Notably, the principles include not only the protective elements of privacy and security but also the principles that guide the active use of AI, such as education, fair competition, and innovation.

Japan’s AI regulations[20] can be classified into two categories: (1) Regulation on AI: Regulations to manage risks associated with AI; (2) Regulation for AI: Regulatory reform to promote the implementation of AI.[21]

The latest AI Strategy 2022 presents a strategic policy to promote the implementation of AI in society, with the dominant aim to overcome Japan’s social issues and to improve the country’s industrial competitiveness.[22] The strategic objectives of the AI Strategy 2022 are to:

- Establish a system and technological infrastructure that enables Japan to protect the lives and property of its citizens in the face of imminent crises such as pandemics and large-scale disasters;

- Become the world’s most capable country in the AI era;

- Become a top runner in the application of AI in real-world industries and achieve enhanced industrial competitiveness;

- Realise a “sustainable society with diversity”, where people from diverse backgrounds, such as women, foreigners and the elderly would be able to fully participate in and reap concrete benefits from AI despite having different lifestyles;

- Build an international network in the AI field for research, education and social infrastructure and accelerate AI research and development, human resources development, and achievement of sustainable development goals through leadership.

The AI Strategy 2022 aims to achieve multiple outcomes such as resilience, inclusion of diversity, sustainability and creation of business opportunities on a global scale.[23] Prior to setting out its initiatives, it urges its citizens to abandon three main preconceptions on AI and to reframe one’s mindset about AI: [24]

- Moving from “AI substitutes for human work” to “AI cooperates with human”. Instead of thinking that AI replaces human, think of it as humans can minimise their effort and maximize their profits by working with AI.

- Moving from a mindset of “only engineers can understand AI deeply” to “AI can be understood from business cases”. When considering how to use AI, it is not appropriate to assume that only engineers can understand AI deeply, but that even without such engineers, it is possible to understand from many real life examples how to leverage AI products and services.

- Moving from a mindset of “all depends on data” to “It is important to form a loop”. While data is important, it is more important that consideration should be given to forming a continuous cycle (loop) such as collecting data to enhance AI services.

Some AI Strategy 2022’s initiatives to promote AI implementation in society include:

- Breaking the black box nature of AI and resolving concerns. This could be done by increasing the accuracy of AI through technical improvements and improving the reliability of AI systems to enhance the transparency and accountability of AI processing.

- Expanding AI application areas. This is achieved through enhancing data that supports AI utilisation by linking and converting these data in a form suitable for AI and promoting technological development in the integration of cyber security, resulting in effective use of confidential data.

- Focusing on the integration of AI with fields where Japan is strong. For example, focus AI applications in fields such as medicine, drug discovery, materials science, and use AI to address challenges unique to Japan such as healthcare, infrastructure and disaster prevention, and regional revitalisation.

Governance Innovation (2020 and 2021)

As mentioned above, METI takes the position that the government should respect companies’ voluntary efforts for AI governance while providing nonbinding guidance to support or guide such efforts. The guidance should be based on multistakeholder dialogue and be continuously updated in a timely manner. This approach called “agile governance,” is Japan’s approach to digital governance.[25]

These values are encapsulated in the Governance Innovation (“GI”) documents, which provides a framework for the new governance model to realize Society 5.0 from two perspectives: the processes of governance (rule-making, monitoring and enforcement), and the stakeholders of governance (government, businesses, and communities and individuals).[26] The concept of agile governance lies in adopting approaches where goals are shared among stakeholders, and implement methods of governance which are flexible and adaptable to changing circumstances to achieve these goals, instead of applying models where goals and procedures are fixed in advance.[27]

The GI documents identify the governance issues that arises from CPSs which form the infrastructure of Society 5.0. These include the recognition of information technology as a social infrastructure, the need to establish a foundation of trust in cyberspace, managing risks posed by autonomous decisions made by AI, difficulty in predicting and controlling results, difficulty in determining responsible actors etc.

To counter these challenges, the agile governance model seeks to embody the following characteristics:[28]

- Constant analysis of conditions and risks;

- Constant revision of goal setting in accordance with the changes in external conditions and the impact of technology;

- Designing governance systems which upholds the basic principles of transparency and accountability, availability of appropriate quality and quantity of options, stakeholder participation, inclusiveness, appropriate allocation of responsibilities, and availability of remedial measures;

- While implementing governance systems, continuously monitor the status of system operation based on real-time data and other inputs. Additionally, it is imperative that the governing actor properly disclose information to stakeholders;

- Evaluate whether the initially defined goals have been accomplished through the governance system;

- Perform continuous analysis on changes in the conditions or risk landscape in which the governance system operates to identify if these changes necessitate revisions to its goals.

The underlying idea of agile governance would be implemented in various layers of society, which is known as “multi-layered agile governance”. Real-world governance in societies is achieved through interactions between overlapping layers of individual governance mechanisms, such as corporate governance, governance by way of regulations, governance by means of public infrastructures, governance by market mechanisms, and governance by individuals and communities.[29]

To realise agile governance, laws and regulations would have to be designed to overcome the challenges surrounding rule-making, monitoring, enforcement and the scope of geographic jurisdiction. Hence, the government should employ “goal-based” regulations that prescribe the goals to be accomplished, as opposed to “rule-based” regulations that prescribe specific duties of action. This is because under rule-based regulations, the governance approaches that companies can work with are likely to become limited, and this may cause the system design and evaluation processes of agile corporate governance to become nonfunctional. Therefore, in order to achieve agile governance, it is desirable for regulations to be designed through a “goal-based” approach that defines the intentions of the goals that companies should achieve, and leaves the defining of specific goals and the ways in which these goals are achieved in this context up to companies’ discretion.[30]

To bolster businesses’ efforts in agile governance, it is important for government and the private sector to work together to establish rules based on standards, guidelines and other soft laws. This is likely to improve predictability for regulated parties, and make it easier for them—especially for SMEs who may have difficulty procuring sufficient budgets for achieving compliance on their own—to achieve the objectives of the laws. It would be desirable for governments to function as facilitators in these discussions, and fulfil the role of fostering society’s trust in companies by certifying companies who meet the formulated guidelines and standards in certain cases.

AI Governance in Japan Ver 1.1.

AI Governance in Japan Ver 1.1. echoes mainly the same approach from the GI documents in its recommendation on ideal approaches to AI governance in Japan. Although legally binding horizontal regulation is deemed unnecessary at the moment, should these be implemented in the future, it suggests that risk assessment should be implemented in consideration of not only risks but also potential benefits. In doing so, consideration should be given to the possibility that certain risks may be eliminated due to the development of technologies.[31]

Further, it contemplates that there may be cases where it is better for organisations responsible for industry laws to be involved in regulations. For example, in the automotive and healthcare sectors, it is deemed desirable to respect rule-making in the respective sectors by making the most of the existing concept of regulations and design philosophy.[32]

For the most part, Japan’s AI policies are clear, consistent, feasible, flexible and accountable. Despite the numerous initiatives set out above, the underlying position is consistent across multiple versions and types of documents.

Japan’s regulatory framework is significant for its lax and soft law approach to AI, which has enabled the country to catch up in its AI development efforts behind other global powers like the United States and China. While the country is aggressive in its industrial competition and innovation objectives, it nonetheless places a great emphasis on harnessing AI sustainably and for the benefit of humanity, instead of advocating for a “growth at all costs” approach.

Japan’s AI initiatives attempt to address ethical concerns related to AI, such as transparency, fairness, accountability, and societal impact. Efforts are being made to develop ethical guidelines and principles for AI development and deployment. However, in practice, in a lax regulatory environment where the benefits of AI are prioritised over its risks, it may be difficult to assess if companies do abide by these ethical principles of AI, given the lack of regulatory oversight. Japan could strengthen its focus on ethical AI development and regulation by establishing clearer guidelines and standards for AI systems. Implementing mechanisms for independent audits and certification of AI systems could help ensure compliance with ethical standards and build public trust in AI technologies.

Currently, we see efforts by the Japanese courts enforcing ethical considerations. In a case tangentially related to AI, a lawsuit was filed by a restaurant claiming compensations against the company that operates “Tabe Log” restaurant review and booking website, alleging that its sales decreased due to unfairly lowered assessment scores on the site. In that case, the court concluded that the change in the algorithm that determines the rating points constituted an abuse of a superior bargaining position and found liability for damages.[34]

Japan does not have dedicated legislation specifically for AI, but it relies on existing laws and regulations to govern AI-related activities. These include data protection laws, such as the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (“APPI“), intellectual property laws, such as the Patent Law and Copyright Law Act and sector-specific regulations. Japan could enhance its data governance framework and privacy regulations to better protect individuals’ rights and mitigate risks associated with AI-driven data processing. Strengthening data protection laws and enforcement mechanisms, along with promoting data minimization, purpose limitation, and user consent principles, could help address privacy concerns and promote responsible data use in AI applications.

From a societal perspective, Japan’s AI efforts are commendable, as it capitalises on AI’s benefits to address pertinent social and environmental issues such as its ageing population and to meet its sustainable development goals. Its policies and initiatives are also integrated with the Society 5.0 vision that the government has for the Japanese society, which sets the foundation for all its frameworks. Japan’s approach in this regard is especially laudable because it makes a conscious effort not to leave its people and society behind even in its race to develop AI. It is also worth noting how Japan’s approach emphasises a multi-stakeholder stance, representing a very holistic and diverse regulatory environment where various parties could participate in the regulatory landscape, resulting it in becoming one of the most AI-friendly countries in the world.

Japan’s approach to generative AI

Notwithstanding that Japan is taking a similar approach to countries such as Singapore and the UK by applying existing legislation to deal with issues arising from the use of generative AI presently,[35] the rapid evolution of generative AI has prompted regulatory bodies in Japan to take significant strides towards establishing a robust legal framework for generative AI (artificial intelligence) technologies. The Liberal Democratic Party of Japan is spearheading efforts in urging the government to enact comprehensive laws regulating generative AI technologies.[36]

The ruling party AI project team will draft preliminary rules, including penal regulations, for foundation model developers such as Microsoft-backed OpenAI.[37] The proposed framework suggests penalties for violations, underlining the government’s commitment to maintaining the integrity of AI-generated content and applications.[38] This initiative aims to set the foundation for the development and utilization of generative AI within a regulated environment, ensuring that innovation does not come at the cost of spreading misinformation or infringing upon individual rights.

Further, the AI Strategic Committee published “Preliminary Screening of Issues regarding AI” on 26 May 2023. The committee pointed out that compliance with existing laws and guidelines (through risk assessment and governance) should be encouraged. However, where it is impossible to solve the issues under existing legislation, the government and relevant stakeholders should consider the countermeasures, taking into account how the issues are tackled globally.[39]

From a global perspective, Japan chaired the G7 Hiroshima Summit in May 2023, where the “Hiroshima AI Process” was established.[40] Guidelines on the development and use of generative AI were discussed and subsequently published in the Hiroshima AI Process Comprehensive Policy Framework.[41] This included a comprehensive set of elements including (1) the OECD’s Report towards a G7 Common Understanding on Generative AI (the “OECD’s Report“), (2) International Guiding Principles, (3) International Code of Conduct and (4) project-based cooperation on AI.[42]

Based on the G7 Hiroshima Process AI documents, Japan released draft AI Guidelines in December 2023. The human-centric principle under the draft Guidelines emphasises that business operators should make sure that they do not violate human rights guaranteed by Japan’s Constitution or internationally recognised rights during the development, provision and use of AI systems.[43] The guidelines for advanced AI systems encourage business to comply with the G7’s International Guiding Principles and the International Code of Conduct.[44]

On January 23, 2024, the Japan Agency for Cultural Affairs (“ACA“) released its draft “Approach to AI and Copyright” for public comment, to clarify how ingestion and output of copyrighted materials in Japan should be considered.[45] The committee embraced Article 30-4 of the Copyright Act, allowing the ingestion and analysis of copyrighted materials for AI learning to promote creative innovations in AI. It removes the need of acquiring consent from copyright holders, if it would not have a “material impact on the relevant markets” and that the AI usage does not “violate the interests of the copyright holders”.[46]

An analysis of Japan’s regulatory approach towards generative AI shows that Japan is cognisant of the fact that it is perceived as lagging behind global leaders on the generative AI arms race. It therefore appears sensible that Japan is adopting an aggressively laissez-faire approach to copyright infringement in the AI space.[47] Although the thought process is reasonable and arguably beneficial for the Japanese economy – to develop Japan’s LLMs quickly without unreasonably harming individual content creators’ ability to make money – in practice, this move is likely to suffer a backlash from content creators as they are deprived of their copyright, and are increasing vulnerable to having their work exploited and used without compensation.

Beyond intellectual property issues, generative AI regulatory policies would also need to consider other complex legal issues, including data privacy and liability and accountability issues, for which there is still no specific legislation providing for AI-related issues in Japan. Given that Japan is still in its early stages of implementing regulations for generative AI, it may seem that its regulatory development in this space is rather piecemeal at the moment.

What is significant about its regulatory strategy presently is the departure from a very “hands-off” approach in regulating traditional AI to a more regulated approach in regulating generative AI. As set out above, the approaches are in quite stark contrast to one another, with Japan adopting impact-based law enforcement where the authorities are reluctant to impose uniform penalties such as administrative sanctions or disqualification and preferring to leave it to the market to self-regulate, to now authorities actively pushing for penalties to be considered as a form of enforcement in the generative AI space. Within a short span of time, one can observe the contrasting attitude towards generative AI by the very same authorities who have previously adopted a very “soft law” approach to regulating traditional AI.

However, some aspects of Japan’s regulatory stance are still uncertain given conflicting sources. Some sources shared that Japan is considering introducing penalties to regulate generative AI as stated above, but there are also sources which indicate otherwise.[48] Perhaps more time and public consultation is needed before Japan is able to come up with a consistent and robust framework in relation to its regulatory stance on generative AI, on whether it would decide to impose penalties for noncompliant players.

Despite news of Japan’s ruling party considering introducing penalties to regulate generative AI, this paper is of the view that ultimately the government would still prefer a market approach like before given the Japanese’s long-standing cultural preference of soft law. This would also better align with its regulatory initiatives in the traditional AI space. Such an approach would be more palatable and attractive for businesses in the technological and AI sectors, where they are already accustomed to a certain regulatory landscape in Japan. Ultimately, it is suspected that Japan’s economic growth and industrial competitiveness would be the priority and dominant consideration to triumph all other regulatory considerations, as Japan itself recognises that it is behind other advanced economies like China and the United States in the AI field.

It may sound slightly cynical, but it would not be unreasonable to speculate that the regulatory plans announced by the Japanese ruling party in relation to generative AI is fuelled more by political considerations to appeal to a conservative Japanese society rather than a genuine hard-handed approach. This is highly plausible in the generative AI space where there is international pressure for Japan to be seen as a global leader in doing something about a technology that is extremely novel, rapidly developing and one which most jurisdictions are taking a cautious approach towards, particularly in light of the enactment of the EU AI Act. That said, one awaits further development in the field of generative AI to see which direction regulatory initiatives would develop in Japan.

Conclusion

Japan’s nuanced approach to AI regulation serves as an interesting case study on balancing innovation, societal impact, and public trust. While its hands-off stance on traditional AI has enabled rapid technological progress, the country’s evolving stance on generative AI highlights the challenges of adapting governance frameworks to fast-paced technological disruptions. As Japan continues to refine its strategies, it will be important to monitor whether its preference for soft law and market-driven approaches can adequately address the complex ethical, legal, and privacy challenges posed by advanced AI systems. Ultimately, Japan’s AI regulatory journey highlights the importance of regulatory agility, multistakeholder collaboration, and a forward-looking, human-centric vision to harness the transformative potential of AI while mitigating its risks. The lessons learned from Japan’s experience offer valuable insights for policymakers worldwide grappling with the challenges of governing transformative technologies.

Editor’s note: This student’s paper was submitted for assessment in end-May 2024. Information within this article should therefore be considered as up-to-date until that time. The views within this paper belong solely to the student author, and should not be attributed in any way to LawTech.Asia.

[1] The Straits Times, “Unlocking AI potential in Japan: Insights for investors and innovators” (26 February 2024) <https://www.straitstimes.com/business/invest/unlocking-ai-potential-japan-insights-investors-innovators-jetro> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Rejolut, “The 13 Most Advanced Countries in Artificial Intelligence” <https://rejolut.com/blog/13-top-ai-countries/> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Takashi Nakazaki, “Japan: Artificial Intelligence Comparative Guide” (10 October 2023) <https://www.mondaq.com/technology/1059766/artificial-intelligence-comparative-guide> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[6] Masafumi Masuda and Kohei Wachi, “Artificial Intelligence Law: Japan” (3 January 2024) https://www.lexology.com/indepth/artificial-intelligence-law/japan (accessed 7 April 2024).

[7] Ray P., “An Overview of the Regulation of AI in Japan” (27 February 2024) <https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/overview-regulation-ai-japan-ray-proper-cissp-rlzrc/> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[8] Keerthana Kantharaj, “Why Japan is Opting for a Softer Approach in its AI Governance” <https://www.ceoinsightsasia.com/business-inside/why-japan-is-opting-for-a-softer-approach-in-its-ai-governance-nwid-10633.html> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[9] Ibid.

[10] Inge Odendaal, “Japan’s Strategy for Building a Robust Domestic AI Ecosystem” (12 April 2024) <https://www0.sun.ac.za/japancentre/2024/04/12/japans-strategy-for-building-a-robust-domestic-ai-ecosystem/> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[11] Sam Nussey and Tim Kelly, “Japan leaning toward softer AI rules than EU, official close to deliberations says” (4 July 2023) <https://www.reuters.com/technology/japan-leaning-toward-softer-ai-rules-than-eu-source-2023-07-03/> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[12] Curtis J. Milhaupt, “A Relational Theory of Japanese Corporate Governance: Contract, Culture and the Rule of Law” (1996) Harvard International Law Journal 37(1).

[13] South China Morning Post, “Japan’s plan to become a world leader in AI” (29 February 2024). <https://www.scmp.com/presented/tech/topics/leading-ai-japan/article/3253314/japans-plan-become-world-leader-ai> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Cabinet Office, “Society 5.0” <https://www8.cao.go.jp/cstp/english/society5_0/index.html> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[16] Foreign Policy, “How Japan is Preparing its Students for Society 5.0” <https://foreignpolicy.com/sponsored/how-japan-is-preparing-its-students-for-society-5-0/> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[17] Study Group on New Governance Models in Society 5.0, 2021 Governance Innovation – Redesigning Law and Architecture for Society 5.0 (July 2021)

[18] Supra n 15.

[19] Hiroki Habuka, “Japan’s Approach to AI Regulation and Its Impact on the 2023 G7 Presidency” (14 February 2023) <https://www.csis.org/analysis/japans-approach-ai-regulation-and-its-impact-2023-g7-presidency> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[20] In this paper, “regulation” refers not only to hard law but also to soft law, such as nonbinding guidelines and standards.

[21] Supra n 19.

[22] Secretariat of Science, Technology and Innovation Policy Cabinet office, Government of Japan, AI strategy 2022 (August 2022).

[23] Ibid, at p 19.

[24] Ibid, at p 20.

[25] Supra n 19.

[26] Study Group on a New Governance Models in Society5.0, 2020 Governance Innovation – Redesigning Law and Architecture for Society 5.0(July 2020).

[27] Supra n 17.

[28] Supra n 17.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Expert Group On How Ai Principles Should Be Implemented, AI Governance in Japan Ver 1.1. (July 2021).

[32] Ibid.

[33] Supra n 31, at p 9.

[34]The Asahi Shimbun, “Court orders food review site to pay damages to store for rating change” (17 June 2022) <https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14647220> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[35] Michihiro Nishi, “Japanese Law Issues Surrounding Generative AI: ChatGPT, Bard and Beyond” (2 October 2023) <https://www.cliffordchance.com/insights/resources/blogs/talking-tech/en/articles/2023/10/Japanese-Law-Issues-Surrounding-Generative-AI.html> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[36] Reuters, “Japan’s ruling party pushes for AI legislation within 2024, Nikkei reports” <https://www.reuters.com/technology/japans-ruling-party-pushes-ai-legislation-within-2024-nikkei-reports-2024-02-15/> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[37] Ibid.

[38] Gemini Group, “Japan’s Move to Regulate Generative AI” (20 February 2024) <https://www.geminigr.com/blog/japans-move-to-regulate-generative-ai> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[39] Supra n 32.

[40] Hiroshima AI Process <https://www.soumu.go.jp/hiroshimaaiprocess/en/index.html> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[41] Kizuna, “The Hiroshima AI Process: Leading the Global Challenge to Shape Inclusive Governance for Generative AI” (9 February 2024) <https://www.japan.go.jp/kizuna/2024/02/hiroshima_ai_process.html> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[42] G7 Research Group, “G7 Hiroshima AI Process: G7 Digital & Tech Ministers’ Statement “ (1 December 2023) <http://www.g7.utoronto.ca/ict/2023-statement-2.html> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[43] Daisuke Takahashi, “New global norms on responsible AI beyond the EU: the G7 Hiroshima Process international guiding principles for developing advanced AI systems and its application in Japan” (11 January 2024) <https://www.ibanet.org/G7-Hiroshima-Process-international-guiding-principles-for-developing-advanced-AI-systems-application-in-Japan> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[44] Ibid.

[45] Scott Warren and Joseph Grasser, “Japan’s New Draft Guidelines on AI and Copyright: Is It Really OK to Train AI Using Pirated Materials?” (12 March 2024) <https://www.privacyworld.blog/2024/03/japans-new-draft-guidelines-on-ai-and-copyright-is-it-really-ok-to-train-ai-using-pirated-materials/>

[46] Ibid.

[47] John Donegan, “The US should look at Japan’s unique approach to generative AI copyright law” (24 February 2024) <https://insights.manageengine.com/artificial-intelligence/the-us-should-look-at-japans-unique-approach-to-generative-ai-copyright-law/> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[48] Japan Times, “Japan’s generative AI guidelines to carry no penalties” (24 November 2023) <https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/11/24/japan/politics/generative-ai-guidelines-no-penalties/> (accessed 7 April 2024).

[JL1]Editor: Citation required.

[JL2]Editor: Citation required.

[JL3]Editor: Suggest removing this as principles are not guidelines or standards.

[JL4]Editor: Consider rephrasing, as it sounds odd to say that a court “acknowledged liability”.

[JL5]Editor: Suggest including a conclusion to properly sum-up the article.