Written by Meher Malhotra | Edited by Josh Lee Kok Thong

We’re all law and tech scholars now, says every law and tech sceptic. That is only half-right. Law and technology is about law, but it is also about technology. This is not obvious in many so-called law and technology pieces which tend to focus exclusively on the law. No doubt this draws on what Judge Easterbrook famously said about three decades ago, to paraphrase: “lawyers will never fully understand tech so we might as well not try”.

In open defiance of this narrative, LawTech.Asia is proud to announce a collaboration with the Singapore Management University Yong Pung How School of Law’s LAW4032 Law and Technology class. This collaborative special series is a collection featuring selected essays from students of the class. Ranging across a broad range of technology law and policy topics, the collaboration is aimed at encouraging law students to think about where the law is and what it should be vis-a-vis technology.

This piece, written by Meher Malhotra, seeks to review the extent to which blockchain technology will be effective in managing IPRs. Today, IPR management systems manage intellectual property rights. Nevertheless, over the years, these management systems have not been matching the expectations of IPR owners, as its institutional gaps hamper the ability of such owners to effectively enforce their rights. In light of this, there have been optimistic proposals seeking to replace and improve such a system with the aid of blockchain technology. This, while a viable solution, is easier said than done. Implementing a blockchain-based system has several implications, including gaining legitimacy from courts. In seeking to provide a realistic overview of the extent to which blockchain technology will be effective in managing IPRs, this paper will examine what makes an effective IPR management system and how the blockchain may deliver on that promise.

Introduction

Blockchain technology has become an “unmissable trend”[1] for many industries in the last decade, including the healthcare and real estate industries. In particular, there is little doubt that blockchain’s advent has had a tremendous impact on how information may be stored safely.[2] In a similar spirit, emphasis has also been placed on another arena: intellectual property (“IP”). With the rapid growth of new technologies, IP rights (“IPRs”) are being generated to safeguard these creations.

Traditionally, these IPRs are managed by IP offices (“IPOs”) through management systems.[3] The systems safeguard IPRs by holding records of who registered the IPRs and when they were registered. Despite its simplicity, such systems are not institutionally equipped to meet the expectations of IPR owners who want the system to manage rather than just register IPRs. An example of this is where the system may be inadequate to prevent the infringement of some IPRs, such as copyrighted work, which can be easily reproduced without authorisation.[4]

This brings us back to blockchain. Some scholars have suggested that blockchain technology could be used to address the institutional deficiencies of current IPR management systems.[5] As we will see in this paper, blockchain could serve as a decentralised ledger for managing IPRs and its records can be seen as evidence in court. However, emphasis should be placed on the word “could”. Despite the supposed benefits of blockchain technology, blockchain IPR management systems remain largely theoretical. For instance, in 2020, the World Intellectual Property Organisation attempted to introduce a decentralised and tamper-proof ledger for digital files and certain IPRs, only to shut it down due to its lack of alterability.[6] In other words, putting the theory into practice is often “easier said than done”.[7] Hence, the feasibility of such an alternative needs to be evaluated to see if it can replace or improve the current system. The purpose of this paper is thus to determine the extent to which the blockchain could be effective in managing IPRs.

In Section II, this paper summarises the properties of the blockchain to establish its capabilities. Section III delves into the dynamics of present IPR management systems and lays the groundwork for what an effective IPR system is. Section IV will describe proposed characteristics for a blockchain-based IPR system, as well as the possible benefits of such a system. This section will specifically look at blockchain’s attempt to fill the institutional gaps existing in the current IPR systems. Section V will outline the challenges of using a blockchain management system, reinforcing the idea that this alternative may still be a work in progress. This section will also discuss the proposed system’s viability with courts, mainly drawing from experiences in China, Russia and Singapore. Since IPR management systems aid in the legal enforcement of IPRs, it is critical that courts regard such systems as legitimate. This paper will conclude in Section VI with some final views on the overall efficacy of blockchain IPR systems and whether such systems are truly feasible in practice.

What is the blockchain?

Before going into detail regarding how IPRs can be managed through a blockchain, it is vital to understand what the blockchain is and how it works. Blockchains are based on distributed ledger technology in which a secure, transparent, and time-stamped record of every transaction is reported to users on the platform.[8] As indicated through its name, the blockchain comprises blocks containing the information of each transaction. New blocks can be added, but they must also include information from prior blocks, forming a tamper-proof chain of information.[9] As new blocks are being added, a record of the date and time is also created, known as time-stamping. Further, blockchains provide a trustworthy record by enabling a distributed network of users — users from multiple computers and organisations — to agree on which transactions should be allowed on the ledger. This is known as a consensus mechanism.[10] Once the block is verified, it is added to the ledger and no user can alter the entry.

From this, three prominent features of the blockchain are discerned. First, blockchain ledgers are transparent. With the data being public, it is easily auditable.[11] Each transaction can also be identified by code and is traceable, with everyone having access to the blocks. Second, immutability.[12] One cannot manipulate the data on the ledger. With this, the record’s integrity is assured by the underlying code. Third, for public blockchains, the ledgers are decentralised.[13] This supposedly eliminates the need for a trusted third-party middleman to ensure legitimacy and record-keeping.

While these key features are per se desirable, to improve the current IPR management systems, these features must also meet the criteria of an effective IPR system. To this end, the next Section explores the current climate of such systems and what makes one effective.

Current IPR management systems

No universal IPR management system exists today. This is because IPRs are territorial in nature: their recognition is generally limited to the jurisdiction in which they are registered. For brevity, rather than explore the limitations of IPR management systems on a jurisdictional basis, the paragraphs below set out common difficulties faced by such systems.

First, although IPR management systems keep records of registered IPRs, they may not be able to match the pace at which those records change.[14] With growing IP commercialisation, IPRs are bought and sold to increase IP portfolio values and raise finances respectively. This means to be effective, an IPR management system must be updated regularly to reflect changes in ownership. Without regular updates, backlogs arise, creating discrepancies between the registered and actual IPR owners.[15] This raises issues in matters of infringement and IP licensing, where proof of ownership is needed. Further, in some countries like Singapore, these systems only record IPRs that can be registered, such as trademarks and patents. This leaves non-registrable rights, such as copyright and trade secrets, unprotected. In these cases, proving ownership can be challenging. This issue is exacerbated with the ease of copying on the Internet.[16] Although digital rights management solutions exist to record and manage non-registrable rights, their accuracy and security are questionable, as these are managed by third parties rather than the rights holders themselves.[17]

Furthermore, with the burgeoning number of IPR registrations, the administrative cost of maintaining and updating IPR management systems can be daunting. The European IPO (“EUIPO”) for example, requires an annual budget of approximately 11 million euros to keep track of patent applications.[18] In turn, these expenses are passed on to IPR owners in the form of expensive registration and renewal fees. Owners also have to wait for a lengthy period for successful registration. This can stifle the first-mover advantage in industries where owners must act quickly to safeguard their inventions against competitors.[19]

So, then, what makes an IPR management system effective? Broadly speaking, “effectiveness” is defined as “producing the result intended”.[20] In the context of IP, an IPR management system is effective when it seeks to advance the core aims of IP law, that is, “to protect the creations of the mind and foster innovation and creativity”.[21] Creators are de-incentivised from innovating when there is slow progress in the way IPs are given legal protection. It is thus likely that effectiveness would be realised more successfully if expenses associated with IPR management systems were reduced through a faster and simpler process.[22] The next Section examines the benefits of a potential solution: blockchain IPR management systems.

The Blockchain IPR management system

The mechanism

Blockchain technology could solve the common difficulties facing today’s IPR management systems,[23] such as by serving as a decentralised ledger for non-registrable IPRs.

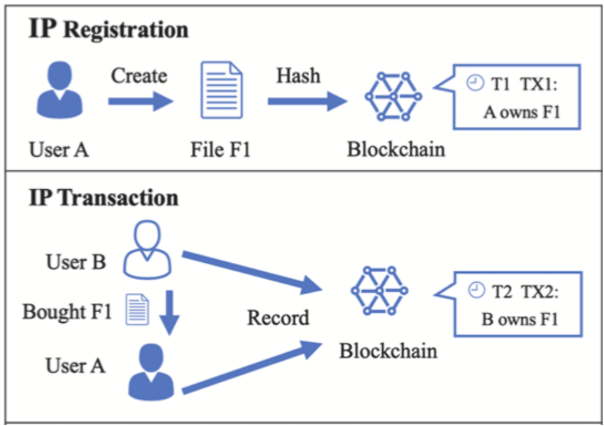

An example of a blockchain IPR management system is IPChain. Launched in October 2016,[24] IPChain uses a public blockchain to record IPR registrations and transactions.[25] One must first submit their official documents regarding an IPR ownership or transaction for authentication. After the data is hashed, it will be sent to the blockchain network to be verified by the consensus mechanism.[26] Once verified, it will be stored on the platform and time-stamped. The process’ visual depiction can be seen in Figure 1. The information in each block will also include a unique identity address, a secret key, a hash value of the original creation’s data, a digital signature and, a sent and approved time-stamp.[27] All of these information can be accessed by users through the platform’s app.

Blockchains generally adopt a “proof of work” mechanism as a consensus mechanism. This is where members must solve an arbitrary puzzle before a new block can be added. However, for blockchain IPR management systems like IPChain, a “proof of contribution” mechanism is adopted. This is where users’ actions are quantified by contribution values calculated by an algorithm.[29] The user with the highest contribution value in each consensus round becomes the bookkeeper by deciding the fate of new blocks. They are also responsible for verifying the block’s information, such as its content and signature.[30] After each round, the contribution value is reset to prevent the issue of monopolisation by one user.[31] This is also different from a “proof of stake” mechanism, which requires users to commit funds to the network, to increase their odds of being selected as a bookkeeper through a “lottery”.[32]

Reasons for adoption

Given that IPOs have adopted databases to ease IPR registration issues, such as EUIPO’s “TMview” system that provides updates on trademark ownership changes,[33] one may wonder about the reasons for adopting a blockchain IPR management system. First, the time-stamping function of the blockchain allows updates to be saved in real-time.[34] Second, blockchain-based systems are decentralised. The bookkeeper can change in each consensus round as the contribution value of a node resets.[35] This means that no external third-party is required to manually update or verify the record. Such features will be especially convenient for trademarks, where owners must demonstrate trademark use and its distinctiveness at several stages of the IPR application’s lifecycle.[36] The registration is made easier by having all these virtually updated and allowing IPR owners to be able to track the process. Third, for certain non-registrable IPRs, an option can be made to upload information privately, without it being visible to anyone. The only way for one to have access is if there is a signed disclosure agreement, which will be recorded onto the blockchain as well.[37] For copyrights, the blockchain can even record and store original works, providing proof of ownership.

Blockchains can also aid in realising IP law’s objective of promoting innovation by improving IP commercialisation practices. IPR owners can utilise the blockchain to attract possible investors while still protecting their creations.[38] The ledger might have a brief description of the creation, while those who want additional details can sign a smart contract. Additionally, IP can also be sold using smart contracts, which can be pre-programmed to self-activate.[39]

In sum, blockchains could help fulfil key needs in managing IPRs by not only filling the institutional gaps in the current system but also by matching IPR owners’ expectations of how the system should manage IPRs. Notwithstanding these benefits, blockchain IPR management systems remain largely as prototypes. The next section explores why deploying blockchain IPR management systems are easier said than done.

Challenges of using the blockchain for IP rights management

There tends to be an exaggeration of the benefits of the blockchain.[40] This was echoed during an Industry Roundtable Discussion on Blockchain and Smart Contracts, noting that while blockchains hold “big promise”, they create “blockages in the progress we can aspire for because the technology in its current state is not perfect”.[41] For example, blockchain’s set-up costs are high, consuming sizeable resources in processing information such as digital documents uploaded by IPR owners.[42] The paragraphs below assess the critical limitations of blockchain technologies.

Blockchain’s immutability has been one of the biggest concerns for its implementation. Although immutability allows for a tamper-proof design, it is virtually impossible to rectify records. Since removing content such as any infringing registrations is against the blockchain’s fundamental principles, mechanisms that provide notice to the users before taking down any content (“notice-takedown mechanisms”) are needed.[43] Additionally, this provision is crucial as the system manages rights, whose ownership and validity can change with court decisions. If not for this mechanism, in the words of Alexander Savelyv, “blockchain will become the enemy of the state and not its ally”.[44] Another way is to employ “super-users” who are government authorities with modification rights.[45] However, such employment plunders the public platform from one of its main features: decentralisation.

Further, having an open platform is another issue as individuals can pose as attackers, submitting ownership documents under their name. How then do we place liability on such perpetrators for violating the owner’s right?[46] What about situations in which smart contracts are breached? Will the system be able to provide contractual remedies? As mentioned by Balàzs Bodó, while blockchains may be effective at protecting informational validity on the ledger, they may not allow examination of the information’s provenance when it is first added into the system.[47]

There are also regulatory difficulties. Blockchain technologies are shaped by their code. Michèle Finck noted that the normative nature of computer code governs the behaviour of those that engage in it.[48] This means that unless there are external legislative constraints, these platforms will often disregard users’ interests. This can be visualised with blockchain systems, where there might be an inadequate framework to tackle issues such as the prohibition of illegal transactions. Further, with such internal codes, even if illegal transactions are removed, perpetrators may face no consequences. Regulators need to define standards for the platform, for it to reach a legitimate system that IPR owners can trust.[49]

Even if regulations are enforced, the ultimate touchstone of effectiveness remains whether such systems are recognised by courts: are courts ready to accept these blockchain records as evidence, especially when there is no centralised system?[50] This has several implications, one being that this compatibility determines whether IPR ownership recorded on a blockchain ledger is sufficient proof for enforcement purposes. Currently, given the novelty of blockchain IPR management systems, there is little precedent available. Nevertheless, recent experiences in China, Russia and Singapore may be of guidance.

In China, blockchain’s potential for recording evidence has been recognised in a recent Chinese decision: Hangzhou Huatai Media Culture Media Co., Ltd v Shenzhen Daotong Technology Development Co Ltd.[51] In this case, the defendant had published the plaintiff’s article on their website without obtaining a license. To prove its claim, the plaintiff showed screenshots of the website that were preserved on a blockchain. To determine whether blockchain-based evidence could be admissible, the court examined whether the plaintiff and the blockchain platform provider were unaffiliated and confirmed the integrity of the platform’s methods of storing evidence. From this, the plaintiff prevailed, with the court holding that the blockchain’s features of “tamper-proof design and traceability” allows for the “preservation, fixation and extraction of e-evidence.”[52]

Notwithstanding the momentous recognition afforded to blockchain-based systems in China, judicial attitudes differ across jurisdictions. Russia, for example, does not recognise blockchain records as admissible evidence in court. This is due to the lack of a legally defined definition of an electronic document as evidence.[53] In particular, there are no specifications as to what features the document should have or what principles of use should be followed for the document to be identified as admissible evidence.[54]

In contrast, in Singapore, Explanation 3 of Section 64 of the Evidence Act[55] allows for the admissibility of electronic records as primary evidence, provided that the records accurately reflect the original document. In the case of blockchain, one might plausibly rely on this to prove that a record in a blockchain is admissible. However, it should be noted that Illustration (a) of Section 64 further provides that such records must be “manifestly or consistently acted on or relied upon”. This may make older records deeper in the blockchain more admissible than recent records.[56]

The final Section evaluates the extent to which this new system will be effective in managing IPRs.

Evaluation and conclusion

Since blockchain IPR management systems are still novel, it remains relatively untested in the IP landscape. While some proponents buoyantly propose the use of blockchain as an IPR management solution, this author prefers a realistic assessment of the extent to which employing such technology is effective in managing IPRs.

While blockchain IPR managements systems can, in theory, serve IP law’s goals of stimulating creativity and innovation by simplifying IPR registration and assuring creators that their works will be protected, in reality, such solutions remain works-in-progress. While some jurisdictions have demonstrated willingness to recognise blockchain records as admissible evidence, the case of Russia shows that the recognition is not uniform. Further, these developments remains some ways off from the full recognition of records on a blockchain-based IPR management system. Furthermore, transiting to such systems will be difficult. Old records would either need to be transferred into the new system, or both systems would need to be interoperable. IPR owners and IPOs would also have to acquaint themselves with such technical knowledge.

Should blockchain IPR management systems be needed in the future, it would be prudent for IPOs to test the waters by implementing a blockchain pre-register, allowing IPR owners to indicate their priority in registration while the actual process is completed.[57] IPOs can also try permissioned blockchains, allowing them to retain some control.[58] Ultimately, while the blockchain may present a viable solution to managing IPRs, IPOs must address its teething issues before they can reap its benefits.

This piece was published as part of LawTech.Asia’s collaboration with the LAW4032 Law and Technology module of the Singapore Management University’s Yong Pung How School of Law. The views articulated herein belong solely to the original author, and should not be attributed to LawTech.Asia or any other entity.

[1] Jun Lin et al., “Blockchain and IoT-based architecture design for intellectual property protection” (2020) 4(3) International Journal of Crowd Science 283 at p 288.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Gönenç Gürkaynak et al., “Intellectual property law and practice in the blockchain realm” (2018) 34(1) Computer law and Security Review 847 at p 847.

[4] National Research University Higher Economics, Copyright in the Blockchain Era: Promises and Challenges (Working Paper, WP BRP 77/LAW/2017, 2017) at p 5 (Alexander Savelyev).

[5] Hongyu Song et al., “Proof-of-Contribution consensus mechanism for blockchain and its application in intellectual property” (2021) 58(3) Information Processing & Management Journal 2.

[6] Anne Rose, “Blockchain: Transforming the registration of IP rights and strengthening the protection of unregistered rights” WIPO Magazine (July 2020).

[7] Alvin See, “Blockchain in Land Administration” in Chan Kok Yew, Gary & Yip, Man, AI, Data and Private Law: Translating Theory into Practice (2021), ch 11 at p 253.

[8] Julie Tolek, The Use of Blockchain in Trademark and Brand Protection, JDSupra, 22 June 2021 <https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/the-use-of-Blockchain-in-trademark-and-1929008/> (last accessed: 1 December 2021).

[9] Ibid.

[10] Id.

[11] Daniel Kraus & Charlotte Boulay, Blockchains, Smart Contracts, Decentralised Autonomous Organisations and the Law (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019) at pp 240-71.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Id.

[14] Supra n 3 at p 855.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Abba Garda et al., “A digital rights management system based on a scalable blockchain” (2020) 14 Peer-to-Peer Networking and Applications 2665 at p 2665.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Supra n 3 at p 856.

[19] Miriam Stankovich, Is Intellectual Property Ready for Blockchain, Digital@Dai, 22 September 2021 <https://dai-global-digital.com/is-intellectual-property-ready-for-blockchain.html> (last accessed: 29 November 2021).

[20] Effectiveness, Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries <https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/effectiveness> (last accessed: 1 December 2021).

[21] Supra n 3 at p 856.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Supra n 1.

[24] IP Chain, Information on IPC Offshore Platform, All Crypto Whitepapers, 2016 <https://www.allcryptowhitepapers.com/ipchain-whitepaper/> (last accessed: 1 February 2022).

[25] Supra n 5 at p 3.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Id.

[28] Supra n 5 at p 6.

[29] Id at p 2.

[30] Id at p 9.

[31] Id at p 17.

[32] Supra n 5 at p 3.

[33] Supra n 3.

[34] Supra n 1.

[35] Supra n 5.

[36] Birgit Clark, “Crypto-Pie in the Sky? How Blockchain Technology is Impacting Intellectual Property Law” (2019) Stanford Journal of Blockchain Law & Policy 252 at p 253.

[37] Supra n 6.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Donald Vella et al., “Blockchain’s Applicability to Intellectual Property Management” (2018) 38(1) The Licensing Journal 1 at p 2.

[40] Supra n 7.

[41] Sim Kee Boon Institute for Financial Economics, Blockchain and Smart Contracts (Industry Roundtable Discussion Paper) at p 14.

[x42lii] Ellie Mertens, How blockchain will change intellectual property – copyright, Managing IP (13 March 2018) <https://www.managingip.com/article/b1kbptbj0tcfqr/how-blockchain-will-change-intellectual-property-copyright> (last accessed: 28 November 2021).

[43] Supra n 4.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Id.

[46] Balàzs Bodó, “Blockchain and smart contracts: the missing link in copyright licensing?” (2018) 26(4) International Journal of Law and Information Technology 311 at p 355.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Michèle Finck & Valentina Moscon, “Copyright Law on Blockchains: Between New Forms of Rights Administration and Digital Rights Management 2.0” (2019) 50 International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition 77 at p 78.

[49] Id at p 104.

[50] Roman Amelin et al., “Prospects of Blockchain-based Information Systems for the Protection of Intellectual Property”, (2019) Communications in Computer and Information Science 327.

[51] Hangzhou Huatai Media Culture Media Co., Ltd v Shenzhen Daotong Technology Development Co Ltd. (2018) Zhe 0192 Civil Case, First Court No. 81, Hangzhou Internet Court of the People’s Republic of China, 27 June 2018.

[52] Vivien Chan, “Blockchain Evidence in Internet Courts in China” Vivien Chan & Co Newsletter (2020).

[53] Denis Grigoryevich Zaprutin et al., “Legal Practice in the Blockchain Era: The Use of Electronic Evidence” (2020) 1(1) Journal of Gender and Interdisciplinarity 404 at p 410.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Cap 97, 1997 Rev Ed.

[56] Yeong Zee Kin, “Blockchain Records under Singapore Law” The Singapore Law Gazette Feature (September 2018).

[57] Supra n 4.

[58] Id.