By Josh Lee | Edited by Elizaveta Shesterneva

Supported by: Lenon Ong, Utsav Rakshit, Benjamin Peck, Ong Chin Ngee, Tristan Koh

“In a year when a certain pesky virus turned the world upside down, how can a conference engage, encapsulate and elaborate upon all of the disruption seen in one year?”

This must have been the key question on the minds of the planners of TechLaw.Fest 2020, as they went about organising Asia’s largest law and technology conference. What followed was a signature conference held with a virtually (pun intended) uniquely signature.

In this article, LawTech.Asia will take our readers on a quick recap of TechLaw.Fest 2020, as we look forward to another exciting edition of TechLaw.Fest in 2021. LawTech.Asia is grateful for our ongoing strategic media partnership with the Singapore Academy of Law (“SAL”), and for the opportunity to be a media partner for TechLaw.Fest once again.

Introduction

COVID-19, in a nutshell, has been a significant disruptor to events globally, large and small. Conferences like TechLaw.Fest are no exception. In previous years, TechLaw.Fest was held as a large-scale physical conference. Venues included the Suntec City Convention Centre and the Marina Bay Sands Convention Centre. This TechLaw.Fest, on the other hand, had no physical manifestation.

Nevertheless, the lack of space did not stand in the way. With 6,200 attendees from over 100 countries, 160 speakers, and over 70 panels, dialogues and talks over 5 days (28 September 2021 to 2 October 2021), TechLaw.Fest 2020 had a digital imprint of mammoth proportions.

The intent of this article is to provide a recap of the key highlights, themes and memorable moments of TechLaw.Fest 2020, including its (virtual) user experience.

Main Stage: Law of Technology and Technology of Law

The main stage segment of TechLaw.Fest 2020 focused on the conference’s five major themes: Legal Operations, Technology Law, Future Law, Access to Justice, and Legal Innovation. Each day of the 5-day conference focused on a theme. Participants could experience different formats such as “Leaders Fireside Chats”, Knowledge Cafes, panel discussions, and “Virtual Networking Cafes”. These terms give a sense of scale of the events – fireside chats were usually helmed by top-level executives discussing broader trends, knowledge cafes and panel discussions comprised expert-level participants giving in-depth talks or engaging in dialogue. Virtual Networking Cafes are essentially virtual networking events (covered by the Harvard Business Review in this article) that allow participants to converge and connect on a common topic, in a more relaxed setting. We cover online networking in TechLaw.Fest 2020 further below. We turn next to some of the notable insights shared throughout the five main TechLaw.Fest themes.

Legal Operations

With legal operations being a relatively new, but increasingly discussed notion amongst legal professionals, much of the conversation focused on understanding what it entailed, why it was important, how to implement it, and the impacts that it would have on the legal industry. As former President of the Corporate Legal Operations Consortium (“CLOC“) Mary Shen O’Carroll said in a TechLaw.Fest interview with LawTech.Asia, legal operations “describes a set of business processes, activities and the professionals who enable legal organisations to serve their clients more effectively by applying business and technical practices to the delivery of legal services”, and includes areas such as strategic planning, financial management, project management and technology expertise.

In the panel discussion titled “Avengers … Assembled – The Value of a Multi-Disciplinary Legal Operations Team”, speakers such as Abdul Malik (Partner and General Manager, Oon & Bazul) and Jim Holding (Managing Director, Aldersgate Funding Ltd.) highlighted the importance of legal operations for law firms, given that “law firms are businesses as well”, and the increasing awareness from clients that their business problems can rarely be solved by law firms alone.

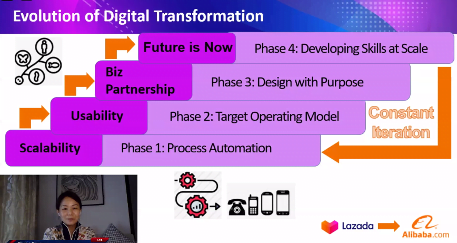

In a separate panel discussion on “Digital Transformation Journeys: The Unvarnished Lessons”, Gladys Chun (General Counsel, Lazada Group) explained that there was a need to think about the way in-house legal departments intersect with the business. She focused on three phases: first, picking areas which can be automated; second, identifying and designing an operating model, and third, using design thinking to design the digital transformation journey.

Technology Law

The second day started with the discussion on copyright law and AI-generated content. During the panel discussion on “Frontier Issues in Intellectual Property”, Professor Lee Pey Woan (Professor of Law, Singapore Management University Yong Pung How School of Law) shared her views on considering consumer rights and competition laws when talking about the work produced by AI. Professor Pamela Samuelson (Richard M. Sherman Distinguished Professor of Law, Berkeley Law School) concluded with the commentary on how algorithms are being trained to produce something “within the genre” (for instance, a Beatles-like song), but not something unique.

The day then moved to a conversation on data protection and cybersecurity laws. These topics have become popular in the recent years, and the point that policymakers in various jurisdictions would face these related issues more frequently was mentioned by both Clarisse Girot (Senior Fellow, Asian Business Law Institute) and Mark Parsons (Partner, Hogan Lovells) in the Knowledge Café session on “Converging Data Protection Approaches”.

Finally, Professor Richard Susskind OBE (Technology Adviser to the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales) and Mark Cohen (CEO and Founder, Legal Mosaic; Executive Chairman, Digital Legal Exchange) talked about transformation mindsets. According to Prof Susskind, “we should ask a fundamental question: what are we training our young lawyers to become?”. Both Prof Susskind and Mark agreed that the redeployment of lawyers will likely transform in the future where the concept of viewing clients as customers will emerge.

Future Law

This theme focused on emerging areas of technology law and regulation, such as AI and emerging regulatory issues post-COVID-19.

In a roundtable on “Applying Ethical Principles for AI and Autonomous Systems in Regulatory Reform”, Gilbert Leong (Senior Partner, Dentons Rodyk & Davidson LLP) highlighted 8 ethical principles that appeared to be gaining consensus globally in regulating AI systems. These were: (a) non-violation of human rights; (b) managing the effects of AI throughout the AI lifecycle; (c) minimizing effects on the well-being and safety of people; (d) controlling the risks on the well-being and safety of people; (e) accounting for social and moral context of areas of deployment; (f) transparency of decisions of an AI system; (g) ensuring that designers and deployers are accountable and able to held accountable; and (h) handling data to be collected by and trained on AI to be handled with care.

Malavika Jayaram (Assistant Professor and Lee Kong Chian Fellow, Singapore Management University Yong Pung How School of Law) urged policymakers and technologists to consider how we could create AI systems that can benefit countries that have the least to do with creating it, while Yong Lim (Associate Professor, Seoul National University School of Law) noted that there was a need for bottom-up and process-driven approaches to AI regulations, including having checks and balances that are integrated into AI systems.

In a Knowledge Café on “Why Robot? Liability for AI System Failures”, members of the Robotics and AI Subcommittee of the SAL Law Reform Committee discussed issues pertaining to legal liability when autonomous systems cause harm to humans. Charles Lim (Co-Chair, Robotics and AI Subcommittee), for instance, noted that “the unique ability of autonomous robots and AI systems to operate independently without any human involvement muddies the waters of liability … including the AI system’s underlying software code, the data it was trained on, and the external environment the system is deployed in”. In respect of driverless vehicles, panellist Beverly Lim (Member, Robotics and AI Subcommittee) noted that one actor who should not be found liable in most cases is the driver behind the wheel, because he (or she) would have bought the vehicle thinking the AI would be a comparatively more reliable driver.

Access to Justice

The sessions on access to justice focused on how technology could help people access legal and justice-related services and navigate the nuances and pitfalls that could come with adopting technologies in societal-specific contexts. For instance, during the Tech Talks session on “Adopting Technology to Advance the Rule of Law: Stories from Southeast Asia”, Hannah Lim (Head of Rule of Law and Emerging Markets, LexisNexis) placed in perspective the experience of societies that appeared to be relatively slower in the adoption of technology. In particular, she highlighted that when people (or communities) do not behave as we expect them to do (such as in adopting technology), it is not because they are not as educated or capable, but because they are simply behaving rationally in their context.

On the panel discussion of “50 Shades of ODR – Developing a Typology for ODR”, the participants touched on the lessons learnt in implementing online dispute resolution systems (“ODR”) – a timely discussion given the growth of adoption of ODR considering the COVID-19 pandemic. Ban Jiun Ean (Executive Director, Singapore Mediation Centre) set the context by focusing on the key question – bearing in mind “who” one is building an ODR system for. He noted that many ODR systems are built for organisations themselves as the primary customer to automate their internal process, instead of building them for the customer. From a practitioner’s perspective, Lim Lei Theng (Counsel, Eden Law Corporation) also highlighted that there is a need for lawyers to remember to focus on assisting litigants, rather than being caught up with the technology. On a more thought-provoking note, Tan Ken Hwee (Chief Transformation and Innovation Officer (Judiciary), Supreme Court of Singapore) highlighted the trend towards having algorithms take over a greater proportion of decision-making in ODR systems, and asked, “Are we risking code becoming law by abdicating the need to find real consensus by leaving decision-making in ODR systems to algorithms?”

Legal Innovation

The final day on legal innovation focused squarely on the use of technology and innovative roadmaps in the legal profession. The marquee session was the closing event of TechLaw.Fest, which saw Singapore’s Second Minister for Law Edwin Tong SC announce the Ministry of Law’s Technology and Innovation Roadmap 2030 for the legal industry. Developed through brainstorming sessions with 90 stakeholders, Minister Tong explained that the Roadmap addressed 4 key questions: (a) What are the key global trends today that have the most impact on the legal industry; (b) How will businesses’ demand for services change in the context of these trends; (c) how can the industry marry the outcome demands with the types of technology solutions available; and (d) how can the government work with various stakeholders to support legal professionals. With these four questions, the Roadmap would answer how transformation in the legal industry could be made efficient and sustainable in the long-term. Minister Tong also clarified that the duration of 10 years was chosen to “give maximum headroom to find new equilibrium with the presence of technology”.

Dealing with the ever-constant fear that technology could replace lawyers, Minister Tong also shared his view that rather than removing jobs, technology would increase the efficiency of legal professionals to high-value work. He expressed confidence that commercial savviness, cultural sensitivities, communication and advocacy skills were not traits or abilities replaceable by computers.

Following the announcement, the Asia-Pacific Legal Innovation and Technology Association (“ALITA”) also released its “State of Legal Innovation in the Asia-Pacific” (“SOLIA”) Report 2020, Legal Innovation Strategy Toolkit, and the world’s first Legal Technology Observatory. ALITA also hosted a Virtual Networking Café on “APAC’s Common Aspirations for Legal Innovation and Technology” which saw TechLaw.Fest attendees vote on the aspirations that most resonated with them to guide how ALITA’s work to unite the Asia-Pacific legal technology ecosystem should proceed in the years ahead.

Other features of the virtual TechLaw.Fest 2020 experience

The proliferation of virtual connectivity tools over the last year has given rise to the saying that “people live in boxes” – a reference to the video screen boxes seen in applications like Zoom and Microsoft Teams. This appears to be an inescapable reality (for now) that highlights the difference between virtual and in-person connectivity. Nevertheless, the question was how an event like TechLaw.Fest 2020 could transcend and deliver a wholly virtual and seamless experience replicating the buzz from in-person conferences.

To that end, it is clear that the conclusion arrived at by the TechLaw.Fest organisers was: replicating the buzz of in-person conferences could not the same as virtually replicating an in-person conference wholesale. This is sensible. After all, the fact that speakers, exhibitors and attendees would be dialing in remotely from different environments and time-zones meant that a virtual conference could not simply be “business-as-usual”. Building buzz must bear in mind the context in which it is situated.

A large part of the answer came from the gamification feature. The idea is simple: participants gain points from interacting with the TechLaw.Fest virtual space, as well as within each other. The more points you earn, the better the chance you have of winning a prize. The key to its success was to integrate the feature into all aspects of TechLaw.Fest. Simply creating and filling your conference profile would already gain you points, ensuring you started out of the blocks with some points already in your pocket. From there, anything from attending conferences, asking questions, replying to others’ questions, visiting exhibitors’ booths, sending direct messages and attending virtual networking sessions would gain you points. This created a virtual virtuous loop that would always keep participants purposefully engaged. It seems to have worked. According to statistics from the organisers, 20,300 conversations and messages were posted over the conference’s 5 days – nearly 200 every hour (over 24 hours)!

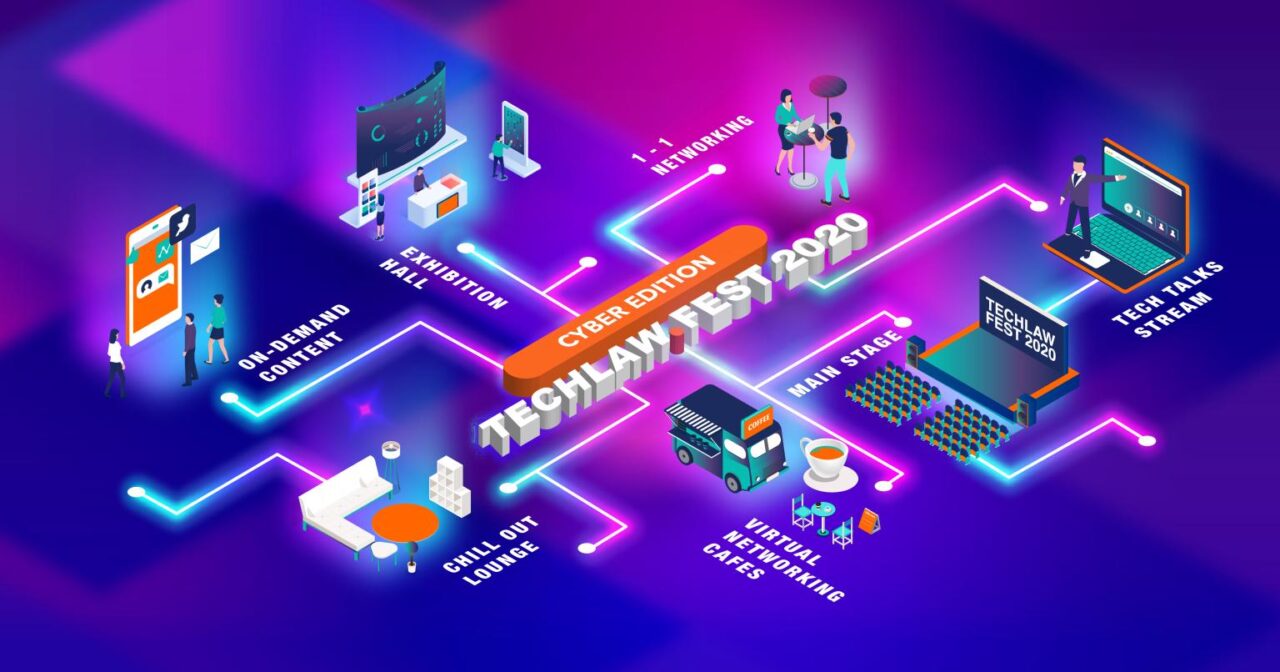

Below the gamification layer were more familiar features. Entering into the TechLaw.Fest virtual zone, participants would see the main stage, a virtual exhibition hall, a networking space, a videos-on-demand section, and a virtual lounge. The virtual exhibition hall featured a nifty trick – rather than list all of the exhibitors on a single (impersonal) page, TechLaw.Fest featured all exhibitors on a map of a virtual exhibition room – complete with booth and logo stands, floors and staircases! Instantly, this created an impression that one was in a closed public setting that one could roam around at will. The networking space allowed attendees to search for fellow attendees by name, industry and interest. The videos on-demand section allowed attendees to watch videos from noteworthy speakers specially curated by the organisers. Last but not least, the virtual lounge provided a space within the TechLaw.Fest ecosystem where attendees could take a break by tuning in to music and music videos (no cat videos, thankfully).

Behind the hood, the conference was spread out over the length of an entire day, which allowed attendees from different time zones to catch a piece of the action. Blocks of time broke up sessions on the main stage, serving as rest periods for attendees to explore the rest of the TechLaw.Fest ecosystem.

Attendees also had access to an in-system personal calendar which allowed one to curate his/her own schedule of interesting talks. The calendar could even be downloaded offline. In talks, attendees could post questions and reply, and even share polls and files. Perhaps most importantly, all content was available asynchronously, which meant that one could catch up on a missed session at any time (especially given the 5-day span of TechLaw.Fest).

Concluding observations

In all, it was hard not to be impressed by the scale and variety of the TechLaw.Fest virtual space, and the lengths and level of detail to which the TechLaw.Fest organisers had gone to improve the virtual user experience. While living up to its billing of “the largest ever” TechLaw.Fest, the conference managed to avoid being over- or under-whelming, while being free for all attendees.

More importantly, besides the user experience, TechLaw.Fest did again what it does best – it delivered substantive and impactful thought leadership on the dimensions of the law of tech and the tech of law. Perhaps most crucially, the entire TechLaw.Fest 2020 experience delivers a fundamentally powerful message – if done thoughtfully, purposefully navigating its benefits and limitations, technology can provide a seamless and transformative platform that enhances and elevates the human experience.

As we look towards a slightly different TechLaw.Fest 2021 – one promising to be a “hybrid” experience – one cannot help but look forward to the innovations and impact this signature conference will once again bring.

This coverage was produced by LawTech.Asia as part of our media partnership with the Singapore Academy of Law for TechLaw.Fest.

Featured Photo Credit: TechLaw.Fest