Written by Josh Lee | Edited by Jennifer Lim Wei Zhen, Wan Ding Yao

Introduction

It is a classic Gordian Knot. A legal industry that is highly risk-averse, and heavily reliant on precedents and traditional ways of work. Lawyers who are too occupied with work to generate innovative ideas, let alone implement them. Technology that is believed to be too inaccessible and alien to a profession that is beginning to struggle with disruption. All these, with the backdrop of rising costs, inefficiencies (and long hours), and barriers to access to justice.

The legal industry’s solution to this? The hackathon.

What are hackathons?

The term “hackathon” is a combination of the words “hacking” and “marathon”, and implies an intense, uninterrupted period of programming. More specifically, hackathons are highly-engaged, continuous events in which small teams produce a working software prototype (also known as the minimum viable product) in a limited period of time.

It is unclear where hackathons originated from, or what original form it took. One possibility is that they originated from the culture of the hacking community, in which dedicated teams of hackers worked together over a few days to achieve an objective. Globally, hackathons have spawned wildly popular technology products, including Facebook’s Facebook Chat feature (now better known as “Messenger”), and Instagram’s time-lapse tool Hyperlapse.

Hackathons largely share these key characteristics:

- First, they centre on a common theme (e.g. “increasing access to justice” or “increasing communication”), problem statement (e.g. “how do you embed data privacy in document generation”), or technology (e.g. using machine learning as the technical basis of a product).

- Second, they have a fixed starting and stopping times, within which teams will have to create a demonstrable version of their idea. Within this period, organisers also aim to provide everything the teams need in order to code without interruption, such as a stable Internet connection, onsite technical support, and refreshments.

- Third, they often include a demonstration segment (“demos”) in which teams have a few minutes to pitch and showcase their prototype, explaining what it is and why they developed it. Most demos show only a small number of working features, as the aim is to demonstrate their idea’s value through a proof of concept. The most successful demos are easy to understand and demonstrate the key aspects of a novel idea.

- Fourth, they often involve multi-disciplinary teams, with the best products often developed by specialists in different fields. For instance, teams could include the following roles: an expert in the subject-matter in which the theme or problem statement arises (e.g. a doctor in a medical technology hackathon), a software engineer or coder to build the prototype, and a business / marketing expert who decides how to best pitch the technology to the judging panel.

The legal hackathon

Legal hackathons are essentially hackathons organised around a theme or problem statement relating to the legal industry. As with other hackathons, legal hackathon teams often do not just comprise of lawyers, but also of developers, designers, marketers and entrepreneurs. Teams come together for a few days, and in a sustained burst, create technological solutions aimed at tackling some of the legal industry’s most vexing problems.

In our view, legal hackathons have the potential to address some of the key chronic problems facing the industry:

- The format of legal hackathons is the anti-thesis of the traditional legal working model. Instead of having lawyers work only on one aspect of the problem, with work being created by juniors and vetted or approved by seniors, legal hackathons emphasise on cross-disciplinary collaboration. In such a setting, legal is only one aspect of the larger problem. Further, with the limited amount of time available during the hackathon, the lawyer’s traditional mindset of being risk-averse merely hinders, rather than enables. In addition, with hackathon-ers expected to tackle complex, multi-faceted problems, there simply is no precedent book. In short, legal hackathons reshape lawyers’ approaches towards legal work.

- Related to point above is cross-disciplinary collaboration. In the 20th century, businessmen dealt with business concerns, while lawyers dealt with legal problems. Today, as any lawyer will tell you, that concept is wholly outdated for the 21st century legal profession. In this regard, legal hackathons expose legal professionals to ideas from other industries, encouraging the cross-pollination of ideas. They also challenge lawyers to find innovative ways to explain legal concepts and issues to coders and marketers in a simple and understandable manner. In turn, lawyers are forced to think from alternative perspectives in order to create solutions that not only address the problem statement, but are also technically sound, make business sense, and are intuitive and well-designed.

- Legal hackathons also encourage legal professionals to focus on confronting a particular problem statement, consider what a user may want, think of intuitive designs, and assess how a solution could work from the user’s perspective. In other words, legal hackathons force legal professionals to confront innovation directly and thoroughly. For the few days (and sleepless nights) of the hackathon, legal professionals have to suspend all other concerns and focus solely on making innovation possible.

The LIT Hackathon

The LIT Hackathon is a recent example of such a hackathon. The LIT Hackathon was organised by the Legal Innovation and Technology student club (“LIT”) of the Singapore Management University (“SMU”), in conjunction with the Singapore Academy of Law (“SAL”) and Rajah & Tann Technologies (“R&TT”). Held from 1 to 3 February 2019, the Hackathon saw 50 students from legal and IT-related disciplines (making up nearly 20 participating teams) vie for top prizes. LawTech.Asia covered the LIT Hackathon as its official media partner.

Over 36 hours of intense planning and coding, the teams tackled one of 12 legal industry problem statements curated by SAL. Examples of these problem statements include: (a) raising awareness of individual legal rights; (b) providing individuals with information on lawyers; and (c) making legal research less tedious and more efficient.

The teams and their technological solutions were then assessed by an illustrious judging panel. The panel comprised: Mr Yeong Zee Kin (Assistant Chief Executive of the Infocomm Media Development Authority); Mr Tan Ken Hwee (Chief Transformation & Innovation Officer of the Supreme Court of Singapore), Mr Rajesh Sreenivasan (Partner at Rajan & Tann LLP and Director of R&TT); Mr Michael Lew (Chief Operating Officer of R&TT) and Mr Garrett Teoh (Director at Accenture).

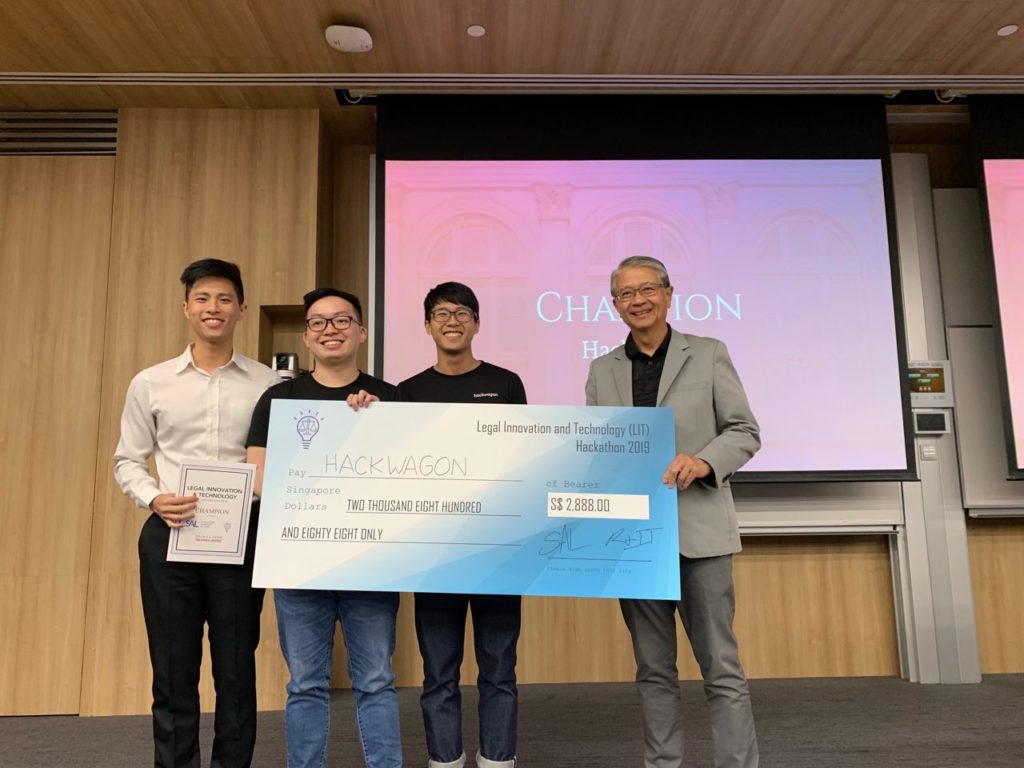

(Photo Credits: LawTech.Asia)

Eventually, the following teams won top honours at the Hackathon —

- 1st Prize: Team Hackwagon (Ng Jun Xuan, Ian Lam and Kong Yu Jian), with the Oversight platform;

- 2nd Prize: Lawgic (Glenice Tan, Wan Ding Yang, Carolyn Au and Nicolas Wee), with the LegalMe bot;

- 3rd Prize: Team Super Spuds (Sambhavi Rajangam, Nur Shukrina binte Abdul Salam, Abhyuday Samadder and Chung Jia Hui Joey), with the Legal Kaki platform; and

- Special recognition prizes (for the teams that made the best use of the LawNet Application Programming Interface (“API”): Team Lawgic, and Team Law-L.

(Photo Credits: LawTech.Asia)

Team Hackwagon – Oversight

Team Hackwagon’s Oversight platform aimed to improve the workflow of conducting research, allowing teams of lawyers to collaborate digitally and in real time on research. The team also allows lawyers to easily refer to past research done by previous lawyers in the firm. On top of it all, Oversight included LawNet integration, thus allowing legal research to be done from within the platform.

During their demonstration, the team also showcased the following additional capabilities of their platform:

- Lawyers would be able locate and export cases researched in the past. Points highlighted in these cases would be extracted into a downloadable Word document that sets out the case name, the highlighted point(s), and the paragraph in the case in which the point was located.

- Lawyers could also build on notes made by previous team members.

- On top of it all, lawyers could also view the research from projects being worked on across the whole firm. For sensitive cases or research, however, access can be limited and control with a built-in access control function.

Team Lawgic – LegalMe

Team Lawgic’s LegalMe bot is a bot integrated into the popular messaging app Telegram, which essentially works as a front-end legal search engine for clients. Clients would be able to ask the chatbot questions to allow clients to conduct a self-assessment of their legal issues.

The LegalMe bot also analyses the names of lawyers featured in judgments and automatically generates profiles of lawyers that are notable in a particular field. Hence, for instance, a quick demonstration searching a senior partner in Rajah & Tann showed that the partner had deep experience in commercial litigation before the Singapore High Court and Court of Appeal – substantiating this with the numbers of cases he had been counsel for before each court. According to Team Lawgic, this automated portfolio generation capability would be able to assist lawyers in being able to better showcase their abilities to clients.

Team Super Spuds – Legal Kaki

Also spotting the potential in allow clients and laypersons to search for answers to their legal questions, Team Super Spuds’ Legal Kaki platform included a chatbot that answered legal questions on litigation procedure (in such areas as crime and personal injury). For example, the team showed how lawypersons would be able to use their platform to ask which stage in the litigation process they are currently in. The team also created an online calculator for division of assets pursuant to Syariah law.

Hackathons as a platform for multi-disciplinary collaboration

Above, we explored how legal hackathons could provide a platform for lawyers to engage in cross-disciplinary collaboration. This certainly played out in practice over the course of the LIT hackathon. Several teams shared how it was an eye-opening and innovative experience finding ways for legal and non-legal experts to work together, such as through explaining legal concepts with the use of analogies. Team Lawgic, in particular, shared how their team managed to find a common basis for understanding by drawing out their solution in the form of a decision tree.

Rajesh, having seen the teams present their answers to the problem statements, agreed. He said that allowing law students and coders to begin collaborating would allow them to “create bonds that could stand the test of time” He also shared how, in his view, the LIT Hackathon provided “great exposure for students because it allowed them to see the utility of their solutions from a practice standpoint”, noting that teams that developed solutions “that were not only sound as an idea but worked practically” stood out in particular.

Concluding thoughts

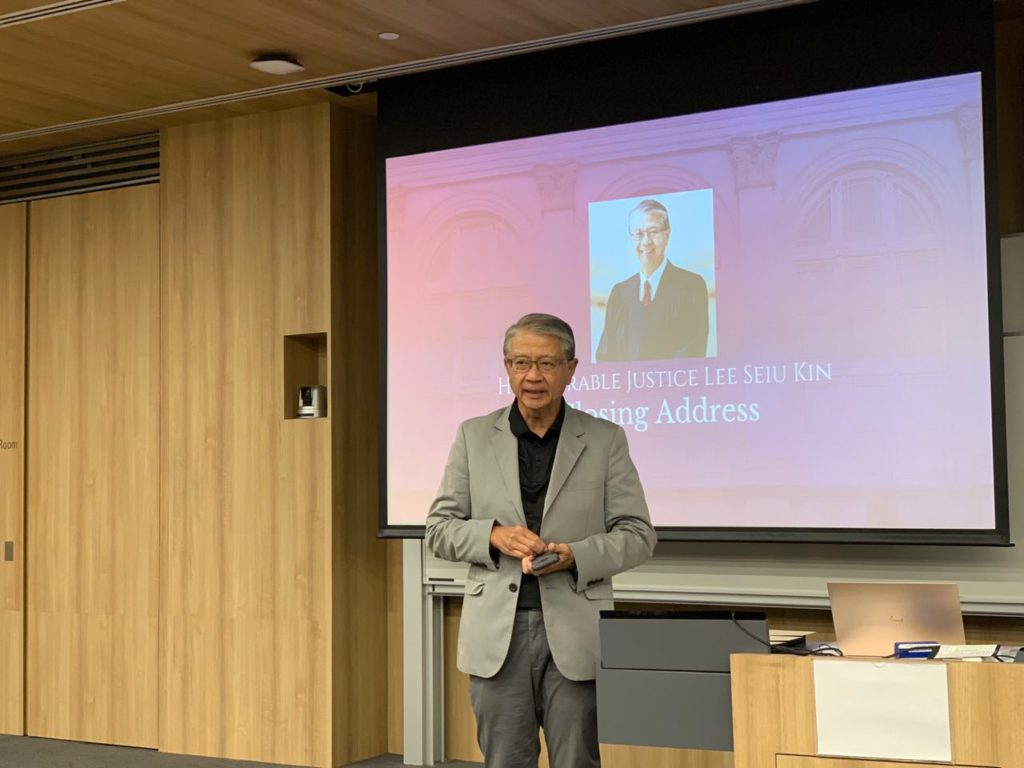

At the close of the Hackathon, Guest of Honour Justice Lee Seiu Kin from the Supreme Court of Singapore highlighted the upcoming disruption and challenges posed to the legal industry by emerging technologies such as AI. Be that as it may, however, Justice Lee reminded the audience that the legal sector in Singapore had “always risen to the challenge”, and he encouraged the students in the room to continue challenging themselves by solving the issues of a digital future. He also called for students to contribute towards efforts to put Singapore on the global legal tech map.

(Photo Credits: LawTech.Asia)

While Justice Lee shared these thoughts with a room filled mostly with students, they would have been equally (if not more) relevant to a room of lawyers. As key stakeholders in the legal industry of the future, lawyers would be well-advised to (as then-Senior Minister for State Indranee Rajah SC put it) “lose the Luddite label … (and) be at the forefront of the future economy”. While hackathons are certainly not the panacea to all the challenges faced by the legal profession with regard to innovation, hackathons certainly allow legal professionals to cut through doubt and embrace the spirit of innovation – thereby cutting through the Gordian Knot of our times.

Addendum: The Global Legal Hackathon 2019 (Singapore National Round)

Not too long after the LIT Hackathon, the legal tech industry in Singapore saw great buzz with the holding of the Singapore national round of the Global Legal Hackathon (“GLH“). Below, we provide a brief update on what recently transpired at the Singapore national round of the GLH 2019.

While the LIT Hackathon saw overwhelmingly positive support from students with backgrounds in law and computing, the GLH saw enthusiastic support from working professionals from around the world. In particular, this year’s GLH saw teams with a remarkably diverse mix of professionals from Singapore, Malaysia, Australia and the US (among others).

The GLH is billed as “the Olympics of legal tech hackathons”. Held annually, the GLH comprises of three rounds: the national round, the regional round and the international round. On 22 to 24 February 2019, participants across 46 cities competed in their respective countries’ national rounds. The GLH Singapore national round, jointly organised by SAL’s Future Law Innovation Programme and Singtel, focused on contract and document review and storage problems which in-house lawyers faced.

At the end of a gruelling 48 hours, the following teams – all of whom focused on how to integrate the contract review process within in-house lawyers’ existing workflows – emerged as winners:

- 1st Prize: Team AcidFyre (Pixie Cigar, Chee Wei Jie, Terence Teoh, A. Jason Velez, Jonathan Quie, Trey Richards, Puay Ni Yi, Milon Goh) with ClauseBot, a web WYSIWYG (“What You See is What You Get”) editor to draft contracts consistently within an organisation. This came with a Microsoft Word plug-in to review contracts.

- 2nd Prize: Team SideKick (Lim Yuan Jing, Adrian Kwong, Eldric Liew, Daniel Chan), with the SideKick platform to review negotiated contracts and flag clauses as to how far it complies with or deviates from company standards.

- 3rd Prize: Team CLAUSIF.AI (Lim How Khang, Liow Jen Nick, Rachel Wong, Jennifer Lim Wei Zhen, Khoo Yong Jie, Yap Jia Qing, Ian Chai, Ruby Pryor), with the CLAUSIF.AI platform which offers Microsoft Word integration to filter contracts by contracting party, classify and review contracts for deviant clauses with 89% accuracy, as well as suggest clauses, powered by an unsupervised machine-learning AI model.

An additional innovative feature of this year’s GLH was a mentoring segment, during which in-house lawyers from Singtel and Lazada, past winners of the GLH, and legal tech entrepreneurs visited and shared industry pain points, workflows and on-site feedback on the workability of their solutions. This also presented a valuable learning opportunity for the teams.

LawTech.Asia warmly congratulates all winners from the Singapore round of GLH 2019, and wishes the winning team the very best in their next steps in the competition.