Written by Josh Lee | Edited by Stella Chen, Micole Yang

Introduction

Predictions of the future often tell us that we will soon have robot housekeepers, cars that drive themselves, and holidays in space. While these may be still some time away, it is already possible today to imagine a future where we no longer think of going to a physical location (the courts) to resolve our disputes. The ongoing revolution in communications technology and artificial intelligence systems may soon allow us to dispose most of our problems with a click of a mouse button.

This article seeks to give a general introduction to our readers about the phenomenon of “online dispute resolution” (“ODR”). This includes: (a) covering the definition of ODR and what ODR generally entails, (b) a brief coverage of current and prominent examples of ODR, and (c) examining the opportunities for ODR in light of growth trends in the region, and what young lawyers and law students can do (now) to leverage on the ODR trend.

The phenomenon of ODR and its growing prominence

While there does not seem to be a universally-agreed definition for ODR at present, ODR can be seen as the resolution of disputes with the use (or aid) of online and Web technology.

Existing conceptions of ODR may involve having hearings online, or simply storing court documents in the cloud (such as the e-Litigation system used by the Singapore courts). In the near future, however, ODR may become a highly-sophisticated venture. Technology could shift from playing a passive role in facilitating dispute resolution, to joining the existing three parties in a dispute (the plaintiff, the defendant, and the judge or mediator) as a “fourth party”. This means that technology will be able to help us find and create custom-made solutions, reveal information at appropriate moments, constructively augment parties’ correspondence, and even match commonly-used solution to commonly-faced issues.

eLitigation: The existing frontier of ODR in Singapore.

With these in mind, the case for ODR has never been stronger.

First, ODR will be a natural extension of the digital revolution, as more of our lives are led online. The result is that people increasingly expect that more of what they do in the physical world should be available online as well – including the resolution of their disputes.

Besides, conventional dispute resolution systems are simply unable to cope with the cross-jurisdictional complexities of cross-border, low-value online disputes. Instead, ODR works the way the Internet does: it avoids thorny issues of jurisdiction, allows redress to be built directly into contracts, and allows dispute resolution through the use of software.

Second, consumers’ demands for dispute resolution are changing, with a focus on speed, rather than success. Surprisingly, research has shown that parties in online disputes seem to be more willing to accept an adverse result received faster, rather than have to wait longer for a result (even if the outcome is eventually in their favour). This is especially so in disputes involving minor online commercial transactions (such as online shopping). It turns out that in the commercial world, knowing a result faster may be more valuable than an actual award (obtained after some delay), because earlier certainty enables faster alternative planning.

Third, the increasing digitisation of society presents an immense opportunity to provide justice to the masses. As observed by Richard Susskind, it seemed to be the case (up to at least a few years ago) that access to justice was only available to people rich enough to pay for it. With ODR processes being fast, fair, and free (or cheap), ODR may vastly improve the ability of justice systems to provide universal access to justice.

Examples of ODR

In the past decade, real progress has been in respect of providing ODR services online. The following examples are prominent ODR initiatives that have made ODR a serious tool in the suite of dispute resolution mechanisms.

(a) eBay

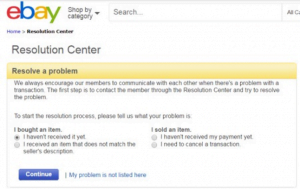

A famous and successful example of ODR widely used today is eBay’s Resolution Centre. This online portal resolves an astonishing 60 million disagreements every year – far more than any conventional dispute resolution system in the world.

This is an astonishing example of what justice systems can do with some assistance from online technology wizardry. By the numbers, up to 50% of all disputes that go through eBay are resolved amicably; 90% of cases are resolved using eBay’s in-house software, without the need for human intervention, and most resolutions never even get appealed in court.

More pertinently, by handling a wide range of civil disputes pertaining to online transactions, including breach of contract claims, and intellectual property disputes, eBay’s Resolution Centre has virtually created a “civil justice system in the cloud”.

A screengrab from Ebay’s Resolution Centre.

(b) Modria.com

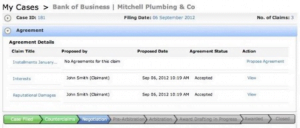

Established in 2011, Modria is a leading modular ODR platform that provides its users with a toolbox, allowing them control and customisability over how they want their dispute resolution process to look like. One can think of Modria as a “buffet table” of ODR tools, from intelligent diagnosis, web-assisted negotiation and mediation (or even arbitration) into one’s dispute resolution process.

Modria has built in various winning qualities, such as an easy-to-use reporting interface for parties, a high-volume case management system, and a Policy Centre for rule-based resolutions. Further, Modria boasts ISO-grade security certifications, ensuring security and confidentiality.

These qualities aside, however, it is Modria’s customisability and comprehensive suite of services offered that has been the key to its success. For example, Modria’s Problem Diagnosis Wizard allows parties to (among other things) pre-emptively diagnose and resolve disputes, deliver automated resolutions, hold private caucuses and conversations online, consult a library of relevant solutions, and even track and evaluate their dispute resolution progress.

Modria’s User Interface. Note the progress bar at the bottom, which allows

users to track the progress of their dispute resolution process.

(c) Governmental forays into ODR: UK, and the EU

The UK Government has been a committed investor in ODR systems. In 2002, the UK’s Ministry of Justice set up an online system dubbed “Money Claim Online”, which enabled users with no legal experience to recover unpaid debts and other monetary claims up to a value of 100,000 pounds, without having to ever set foot in a court. Among other features, the Money Claim Online system allowed users to request a claim online, keep track of the status of a claim, and where appropriate, request entry of judgment and enforcement. This system has been said to handle more than 60,000 claims each year.

Money Claim Online: The UK Ministry of Justice’s ODR initiative.

More recently, the UK has also embarked on one of the largest governmental ODR initiatives in the world. It has amassed a S$1 million war-chest to create the “HMOC” (Her Majesty’s Online Courts) – a virtual courtroom in which disputes below 25,000 pounds can be resolved.

The EU has also made significant inroads into ODR. For instance, on 21 May 2013, the European Parliament passed EU Regulation No 524/2013, to provide for the establishment of a Europe-wide ODR platform allowing for “independent, impartial, transparent, effective, fast and fair out-of-court resolution of disputes between consumers and traders online”. The EU ODR platform went live on 15 February 2016, and now provides EU consumers a single point of entry to consumers and traders to resolve online commercial disputes.

What future lawyers can do to prepare for the ODR revolution in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is on the verge of an e-commerce revolution. The figures are telling – online shopping, accounting for only 1% of retail in 2015, is likely to reach double-digits in the next half of this decade. Eventually, the region of 600 million people could become the third-largest e-commerce market worldwide, surpassing both the US and EU.

This comes on the back of rising internet connectivity in the region. Jim Dougherty, a social media analyst and commentator at Leaders West, reports that the Asia-Pacific region is likely to account for 61% of new Internet users in 2017, a sizeable portion of which will come from developing Southeast Asian countries like Indonesia.

This presents an amazing opportunity for ODR. As consumers shift their consumer behaviour online, they are likely to want their disputes (involving their online transactions) be resolved online as well. In this regard, it may very well be possible for a pan-ASEAN ODR platform to be eventually implemented (as part of the ASEAN Community), similar to EU ODR platform.

In this scenario, young lawyers and law students of the future are likely to need a strong appreciation of ODR as a viable dispute resolution option that is part of a future lawyer’s dispute resolution toolbox. Hence, law students and young lawyers will need to:

- Embrace technological advances. This requires law students and young lawyers to: (i) be comfortable and familiar in utilising ODR; (ii) appreciate online e-commerce models; (iii) understand the likely areas where disputes may arise, and (iv) know what avenues parties can turn to achieve a solution quickly and effectively.

- Know what ODR processes exist. This will mean having to know: (i) the various ODR platforms that currently exist, (ii) the benefits and costs of using certain ODR processes over others (or even over conventional modes of dispute resolution), and, (iii) in more complex disputes, the aspects that can or cannot be dealt with by ODR.

- Pick up new skill-sets pertaining to ODR. Where possible, young lawyers and law students will have to be trained in using ODR, understanding the capabilities and limitations of the intelligent systems in each ODR medium, and systems and process design. The need for our next generation of lawyers to have these new skill-sets is especially important where there is a need to advise clients on how to custom-build ODR processes (such as the options provided by Modria) to meet their clients’ needs.

Conclusion

ODR and more conventional forms of dispute resolution need not be a zero-sum game. ODR merely expands the range of tools available to lawyers to solve their clients’ issues effectively. Ultimately, it is up to the lawyer to “fit the forum to the fuss” to protect a client’s interest and make universal access to justice a reality.

As with all innovations in the legal sector, however, there needs to be a paradigm shift in the mind-sets of lawyers. Lawyers need to realise that what has worked in the 20th century is increasingly inapplicable in the 21st century of digitisation, on-demand services, and tech-savvy clients. In this future, lawyers and law students wedded to traditional forms of thinking will be weeded out, whereas those willing and eager to embrace the coming changes will be presented with more opportunities than they could ever dream of.